Gabriele Lapp, born 25 January 1945

Gabriele's story

Gabriele Lapp grew up near Ludwigsburg in Württemberg. When Gabriele was six years old, a neighbouring child named Marianne told her that her parents were not her “real” parents. At home, she learnt that Marianne was right and that Marianne was also Gabriele’s half-sister and likewise a foster child. They had the same German mother and different French fathers. Gabriele was sad and shocked. She found support in her good relationship with her foster parents, who never spoke badly about her biological parents. At age 17, Gabriele met her future husband Jürgen Lapp. She moved to Hamburg to be with him and they started a family there. During a summer holiday in France in 1977, Gabriele went to the last known address of her biological father, which her mother had given to her foster parents. She stood in front of the door, but did not dare to ring the bell.

After the death of her adoptive parents, she continued her search for her biological family. Using the internet, she found other half-siblings and her mother Maria Rogalski in the United States. However, their first telephone call in 1996 was disappointing for Gabriele, as her mother was not interested in meeting her.

Gabriele Lapp (right) with her half-sister Marianne Bartl, ca. 1950

After Gabriele moved to Hamburg in 1963, she lost contact with her half-sister Marianne. It was not until 32 years later that Gabriele made contact with her again while searching for their mother.

Photo: unknown. Private property Bartl

Gabriele’s foster parents Auguste and Karl Göhringer, 1963

Gabriele had a close relationship with her foster parents. They followed their daughter to Hamburg and adopted her there. Gabriele was 30 years old at the time.

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

Maria Rogalski, early 1950s

After the war, Maria moved to the United States with her second husband Eugene Rogalski without her children. Three more children were born from this second marriage.

Photo: unknown. Private property Bartl

The story of the parents

Gabriele Lapp’s mother Maria already had six children with her husband Wilhelm Dall’Osteria, an SS member stationed in Berlin, when she entered into a relationship with the French prisoner of war Paul H. in 1943. They had a daughter together, Marianne. A year later, Maria was sentenced to prison for “illegal contact with prisoners of war”. She was pregnant with Gabriele when she went to prison. The father was the French forced labourer Noël Q., who worked in a factory near her flat. Maria was released early from prison shortly before Gabriele’s birth. Noël Q. returned to France in April 1945. He married shortly after the end of the war. He never spoke to his family about Maria and their child.

Interview

“I think I have something French in me.”

Dealing with prisoners of war and forced labourers

Some of the prisoners of war in the German Reich were formally released from captivity during the war and assigned the status of “civilian labourer”. The Nazi authorities did so in an attempt to circumvent the Geneva Convention, which granted rights and protection to prisoners of war. Of approximately 1.3 million French prisoners of war, around 220,000 were given “civilian labourer status”. In addition, around 700,000 French civilians were brought to the German Reich for forced labour. The differences in status entailed different regulations for contact with Germans. For example, there were no regulations regarding contact between French forced labourers and Germans. This led to uncertainty among the population and contradictory behaviour by the police, Gestapo, and judiciary.

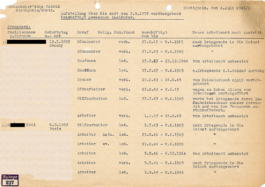

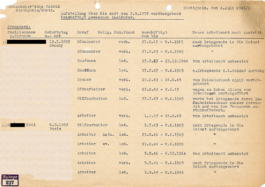

List of foreign forced labourers employed at the Schumacher Factory in Bietigheim in the District of Ludwigsburg during the Second World War, 4 July 1946

Noël Q. had come to the German Reich as a forced labourer in July 1943. He was made to work in the Schumacher factory in the historic district of Bietigheim until 8 April 1945.

Stadtarchiv Bietigheim-Bissingen

Gabriele Lapp, 1961

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

Growing up as an outsider

Gabriele often felt lonely in her childhood and youth. Her social circle was aware that she was the illegitimate child of a Frenchman and a German woman. Parents forbade their children to play with Gabriele because of her background. At school, she had the impression that she received lower grades than others for the same performance. Gabriele was under the custody not of her foster parents but rather of an official guardian. Gabriele does not have fond memories of her guardian’s treatment. He prevented her from getting a higher school leaving certificate. He repeatedly called her in to accuse her of indecent behaviour. However, Gabriele received a lot of support from her foster parents, who repeatedly stood up for her at school and in relations with the guardian.

Guardianship order for Gabriele Lapp, 18 July 1959

Due to the Italian origin of her mother’s first husband, the authorities initially recognised Gabriele as an Italian citizen.

Private property Lapp

Gabriele and Jürgen Lapp at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, 2024

Gabriele and her husband volunteered at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial through the Kirchliche Gedenkstättenarbeit (an organisation of church volunteers) for more than 20 years. They organised tours with visitors and looked after survivors and relatives who visited the memorial.

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

Gabriele Lapp, born 25 January 1945

Gabriele's story

Gabriele Lapp grew up near Ludwigsburg in Württemberg. When Gabriele was six years old, a neighbouring child named Marianne told her that her parents were not her “real” parents. At home, she learnt that Marianne was right and that Marianne was also Gabriele’s half-sister and likewise a foster child. They had the same German mother and different French fathers. Gabriele was sad and shocked. She found support in her good relationship with her foster parents, who never spoke badly about her biological parents. At age 17, Gabriele met her future husband Jürgen Lapp. She moved to Hamburg to be with him and they started a family there. During a summer holiday in France in 1977, Gabriele went to the last known address of her biological father, which her mother had given to her foster parents. She stood in front of the door, but did not dare to ring the bell.

After the death of her adoptive parents, she continued her search for her biological family. Using the internet, she found other half-siblings and her mother Maria Rogalski in the United States. However, their first telephone call in 1996 was disappointing for Gabriele, as her mother was not interested in meeting her.

Gabriele Lapp (right) with her half-sister Marianne Bartl, ca. 1950

After Gabriele moved to Hamburg in 1963, she lost contact with her half-sister Marianne. It was not until 32 years later that Gabriele made contact with her again while searching for their mother.

Photo: unknown. Private property Bartl

Gabriele’s foster parents Auguste and Karl Göhringer, 1963

Gabriele had a close relationship with her foster parents. They followed their daughter to Hamburg and adopted her there. Gabriele was 30 years old at the time.

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

Maria Rogalski, Anfang der 1950er-Jahre

Nach Kriegsende zog Maria mit ihrem zweiten Mann Eugene Rogalski ohne ihre Kinder in die USA. Aus dieser zweiten Ehe sind drei weitere Kinder hervorgegangen.

Foto: unbekannt. Privatbesitz Bartl

The story of the parents

Gabriele Lapp’s mother Maria already had six children with her husband Wilhelm Dall’Osteria, an SS member stationed in Berlin, when she entered into a relationship with the French prisoner of war Paul H. in 1943. They had a daughter together, Marianne. A year later, Maria was sentenced to prison for “illegal contact with prisoners of war”. She was pregnant with Gabriele when she went to prison. The father was the French forced labourer Noël Q., who worked in a factory near her flat. Maria was released early from prison shortly before Gabriele’s birth. Noël Q. returned to France in April 1945. He married shortly after the end of the war. He never spoke to his family about Maria and their child.

“I think I have something French in me.”

Interview

Dealing with prisoners of war and forced labourers

Some of the prisoners of war in the German Reich were formally released from captivity during the war and assigned the status of “civilian labourer”. The Nazi authorities did so in an attempt to circumvent the Geneva Convention, which granted rights and protection to prisoners of war. Of approximately 1.3 million French prisoners of war, around 220,000 were given “civilian labourer status”. In addition, around 700,000 French civilians were brought to the German Reich for forced labour. The differences in status entailed different regulations for contact with Germans. For example, there were no regulations regarding contact between French forced labourers and Germans. This led to uncertainty among the population and contradictory behaviour by the police, Gestapo, and judiciary.

List of foreign forced labourers employed at the Schumacher Factory in Bietigheim in the District of Ludwigsburg during the Second World War, 4 July 1946

Noël Q. had come to the German Reich as a forced labourer in July 1943. He was made to work in the Schumacher factory in the historic district of Bietigheim until 8 April 1945.

Stadtarchiv Bietigheim-Bissingen

Gabriele Lapp, 1961

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

Growing up as an outsider

Gabriele often felt lonely in her childhood and youth. Her social circle was aware that she was the illegitimate child of a Frenchman and a German woman. Parents forbade their children to play with Gabriele because of her background. At school, she had the impression that she received lower grades than others for the same performance. Gabriele was under the custody not of her foster parents but rather of an official guardian. Gabriele does not have fond memories of her guardian’s treatment. He prevented her from getting a higher school leaving certificate. He repeatedly called her in to accuse her of indecent behaviour. However, Gabriele received a lot of support from her foster parents, who repeatedly stood up for her at school and in relations with the guardian.

Guardianship order for Gabriele Lapp, 18 July 1959

Due to the Italian origin of her mother’s first husband, the authorities initially recognised Gabriele as an Italian citizen.

Private property Lapp

Gabriele and Jürgen Lapp at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, 2024

Gabriele and her husband volunteered at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial through the Kirchliche Gedenkstättenarbeit (an organisation of church volunteers) for more than 20 years. They organised tours with visitors and looked after survivors and relatives who visited the memorial.

Photo: unknown. Private property Lapp

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.