Volkmar “Hannes” Harwanegg, born 27 August 1944

Volkmar's story

Hannes Harwanegg’s name is actually Volkmar. His godmother wanted him to have a “primordial German” first name. But because he did not like “Volkmar”, he called himself “Hannes”. Hannes was born in the Austrian capital of Vienna. He grew up with his mother Elisabeth and his stepfather together with five half-siblings. With his black hair and darker skin, he stood out at school. If someone asked him who his father was, Hannes answered as he had been told at home: “I don’t have a father.” When he was about ten years old, his godmother finally told him that his father was Greek. Even though Hannes often asked, he never learnt more about him. It wasn’t until 1995 that he found an old envelope in his mother’s estate with his father’s name on it: Georgios Pitenis. Hannes began a year-long search. He asked archives, colleagues, and even the Greek ambassador for help. During a holiday in Greece in 2006, he finally received a phone call: his father had been found. The following day, he took a taxi to the mountains where Georgios was spending the summer.

Hannes Harwanegg as a baby, 1944

When Hannes was born in August 1944, the Allied bombing of Vienna was just reaching its peak. The hospital where he was born was destroyed a few months later.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

The story of the parents

On Georgios Pitenis’s 22nd birthday, 6 April 1941, the German Reich attacked Greece, as had fascist Italy six months earlier. After a year of German occupation, Georgios was deported to Austria for forced labour. At times he had to dig anti-tank trenches with a hoe and spade—a particularly hard job. In Vienna, presumably on his way to a job site, Georgios got to know Elisabeth. They fell in love and had a secret relationship. When the Second World War ended in 1945 and Georgios returned to Greece, he knew that he had a son. He tried twice to enter the Soviet occupation zone in Austria, where Elisabeth and Hannes lived, but to no avail. Whether Elisabeth also endeavoured to reunite with Georgios is unknown. However, the two kept in touch by letter.

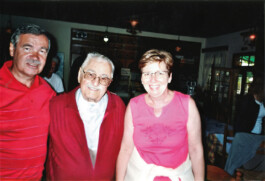

Hannes and his wife at their first meeting with his father, 2006

Hannes Harwanegg visited his father several times in Greece before he died in 2011. Georgios Pitenis’s wish to return to Vienna was never fulfilled.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

Hannes’s mother Elisabeth Wöber, 1984

His mother was always an important person for Hannes. She encouraged his personal, professional, and political development. But she never spoke about his father until her death.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

“My mother and father managed to keep their great love a secret. That’s where I came from.”

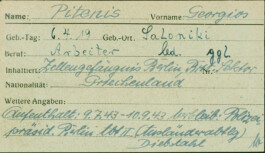

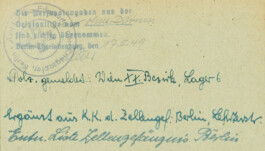

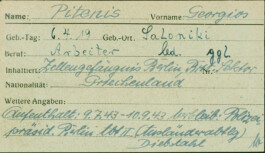

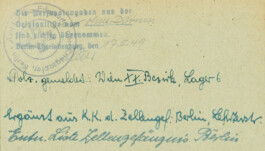

Georgios Pitenis’s entry at the Office for the Registration of War Victims in Berlin, 17 May 1949

Georgios Pitenis spent three months in prison as a forced labourer for “theft”. He never told Hannes about this, saying only that he had been in the resistance in Greece.

Arolsen Archives

Interview

Austria and National Socialism

For Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, the unification of Austria with the German Reich was an important goal. A fascist party had also been in power in Austria since 1933, transforming the country into a dictatorship. However, it wanted Austria to remain independent and even banned the Nazi Party. On 12 March 1938, the German Wehrmacht marched into Austria without resistance. The following day, Austria became part of the German Reich with the Anschluss Act. The Nazi reign of violence was no different in Austria than in the rest of the Reich: political opponents were suppressed, undesirablesin terms of Nazi ideology were persecuted, and

concentration camps were set up. Austrians, who were now legally considered Germans, were just as involved in mass crimes as Germans from the “old Reich”.

Adolf Hitler during his speech at Heldenplatz in Vienna, 15 March 1938

Hitler, himself a native Austrian, announces “the entry of my homeland into the German Reich”. Two hundred and fifty thousand people came to cheer the “Anschluss”.

Photo: unknown. Federal Archives

Event to commemorate the victims of Austrian fascism and National Socialism in Vienna, 2021

Hannes spoke on behalf of the Association of Social Democratic Freedom Fighters, Victims of Fascism, and Active Antifascist.

Photo: unknown. SPÖ Vienna

A life for politics and the culture of remembrance

Hannes joined the left-wing youth organisation Red Falcons as a child. During his apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker, he was a youth officer in the trade union. After attending night school for business training, he worked for a large bank, where his colleagues elected him to the works council. He has been involved in the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) since 1968. From 1993 to 2010, he was a representative in the Vienna state parliament, and for more than 40 years he served as chairman of a local SPÖ association. Through his political work, Hannes got to know former resistance fighters against National Socialism and concentration camp survivors at an early age. Influenced by their stories and his own history, he made the remembrance of Nazi crimes a central task in his life.

Volkmar “Hannes” Harwanegg, born 27 August 1944

Volkmar's story

Hannes Harwanegg’s name is actually Volkmar. His godmother wanted him to have a “primordial German” first name. But because he did not like “Volkmar”, he called himself “Hannes”. Hannes was born in the Austrian capital of Vienna. He grew up with his mother Elisabeth and his stepfather together with five half-siblings. With his black hair and darker skin, he stood out at school. If someone asked him who his father was, Hannes answered as he had been told at home: “I don’t have a father.” When he was about ten years old, his godmother finally told him that his father was Greek. Even though Hannes often asked, he never learnt more about him. It wasn’t until 1995 that he found an old envelope in his mother’s estate with his father’s name on it: Georgios Pitenis. Hannes began a year-long search. He asked archives, colleagues, and even the Greek ambassador for help. During a holiday in Greece in 2006, he finally received a phone call: his father had been found. The following day, he took a taxi to the mountains where Georgios was spending the summer.

Hannes Harwanegg as a baby, 1944

When Hannes was born in August 1944, the Allied bombing of Vienna was just reaching its peak. The hospital where he was born was destroyed a few months later.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

The story of the parents

On Georgios Pitenis’s 22nd birthday, 6 April 1941, the German Reich attacked Greece, as had fascist Italy six months earlier. After a year of German occupation, Georgios was deported to Austria for forced labour. At times he had to dig anti-tank trenches with a hoe and spade—a particularly hard job. In Vienna, presumably on his way to a job site, Georgios got to know Elisabeth. They fell in love and had a secret relationship. When the Second World War ended in 1945 and Georgios returned to Greece, he knew that he had a son. He tried twice to enter the Soviet occupation zone in Austria, where Elisabeth and Hannes lived, but to no avail. Whether Elisabeth also endeavoured to reunite with Georgios is unknown. However, the two kept in touch by letter.

Hannes and his wife at their first meeting with his father, 2006

Hannes Harwanegg visited his father several times in Greece before he died in 2011. Georgios Pitenis’s wish to return to Vienna was never fulfilled.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

Hannes’s mother Elisabeth Wöber, 1984

His mother was always an important person for Hannes. She encouraged his personal, professional, and political development. But she never spoke about his father until her death.

Photo: unknown. Private property Harwanegg

Georgios Pitenis’s entry at the Office for the Registration of War Victims in Berlin, 17 May 1949

Georgios Pitenis spent three months in prison as a forced labourer for “theft”. He never told Hannes about this, saying only that he had been in the resistance in Greece.

Arolsen Archives

»Meine Mutter und mein Vater schafften es, ihre große Liebe geheim zu halten. Daraus entstand ich.«

Interview

Austria and National Socialism

For Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, the unification of Austria with the German Reich was an important goal. A fascist party had also been in power in Austria since 1933, transforming the country into a dictatorship. However, it wanted Austria to remain independent and even banned the Nazi Party. On 12 March 1938, the German Wehrmacht marched into Austria without resistance. The following day, Austria became part of the German Reich with the Anschluss Act. The Nazi reign of violence was no different in Austria than in the rest of the Reich: political opponents were suppressed, undesirablesin terms of Nazi ideology were persecuted, and

concentration camps were set up. Austrians, who were now legally considered Germans, were just as involved in mass crimes as Germans from the “old Reich”.

Adolf Hitler during his speech at Heldenplatz in Vienna, 15 March 1938

Hitler, himself a native Austrian, announces “the entry of my homeland into the German Reich”. Two hundred and fifty thousand people came to cheer the “Anschluss”.

Photo: unknown. Federal Archives

Event to commemorate the victims of Austrian fascism and National Socialism in Vienna, 2021

Hannes spoke on behalf of the Association of Social Democratic Freedom Fighters, Victims of Fascism, and Active Antifascist.

Photo: unknown. SPÖ Vienna

A life for politics and the culture of remembrance

Hannes joined the left-wing youth organisation Red Falcons as a child. During his apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker, he was a youth officer in the trade union. After attending night school for business training, he worked for a large bank, where his colleagues elected him to the works council. He has been involved in the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) since 1968. From 1993 to 2010, he was a representative in the Vienna state parliament, and for more than 40 years he served as chairman of a local SPÖ association. Through his political work, Hannes got to know former resistance fighters against National Socialism and concentration camp survivors at an early age. Influenced by their stories and his own history, he made the remembrance of Nazi crimes a central task in his life.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.