Erika van Santen, born 25 March 1946

Ton Maas, born 26 July 1956

Erika's and Ton's story

Erika and Ton grew up in Eindhoven in the Netherlands. However, a lot of German was spoken and sung at home because their mother was German. The siblings knew that their parents had met in Berlin during the Second World War, but this was rarely discussed in the family. It was important to their mother Martha that her children went to university, as she herself had not been able to do so during the war. Erika studied primary school education. She married her childhood friend Bram van Santen and moved with him to Capelle aan den IJssel, where they started a family. Her brother Ton, ten years younger, first studied astronomy and later business administration. He moved to Mierlo near Eindhoven with his wife Ine van Vijfeijken and their children. When he was 40 years old, he lost his ability to work due to health reasons. In 2016, he began intensively researching the history of his family. In the estate of their father Kees Maas, the siblings found diaries from his time as a forced labourer in Germany, as well as letters from Kees to his parents and from Martha to Kees. Based on these documents, Ton wrote a book about the history of his parents.

“And there was such a tension in our home, I didn’t know what it was, but I felt it.”

Erika

The Maas family, October 1956

Kees and Martha Maas with their three children Peter (left), Erika, and Ton. Peter died in 2011 at

age 61.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

The story of the parents

Born in the Netherlands in 1923, Kees Maas was transported to The German Reich in 1943 as a forced labourer, where he had to work at Telefunken in Berlin. He met 25-year-old German Martha Kopka at the doctor’s when they both wanted to take sick leave, even though they were not ill. They spent the day together and fell in love. When Martha was transferred to Reichenbach, now Dzierżoniów in Poland, they met secretly in Berlin and Reichenbach. With the help of friends and a fake travel permit, Kees even visited Martha in her home village of Alt Hammer (Kuźnica Katowska), southeast of Breslau (Wrocław) in what is now Poland. After the end of the war, they reunited in Ichstedt in Thuringia. Martha became pregnant and they married. Kees returned to the Netherlands and Martha and her daughter Erika were able to join him in 1947.

Martha and Kees on the day of their engagement in Berlin in front of bomb debris, July 1944

The city was the target of Allied air raids, especially in the last three years of the war.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

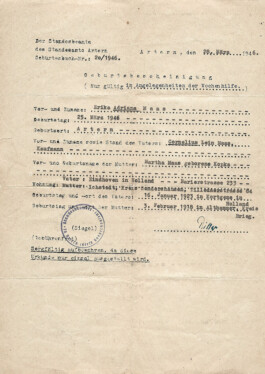

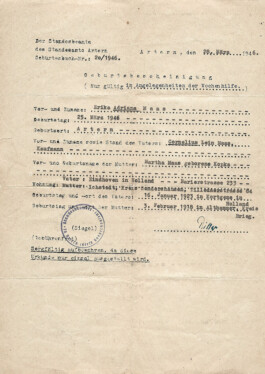

Birth certificate of Erika van Santen, 28 March 1946

Erika was born in Artern,Thuringia, in 1946. In late 1947, Martha Maas was allowed to leave the Soviet occupation zone with her daughter. She followed her husband Kees to the Netherlands, where Peter and Ton were born.

Private property van Santen

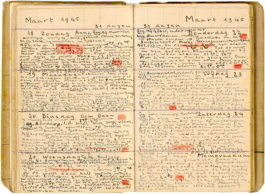

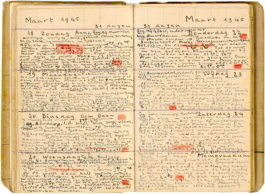

The diary of Kees Maas for the year 1945

Kees recorded observations, encounters, experiences, and feelings during his time as a forced labourer in the German Reich in several diaries. His first encounter with Martha is also recorded in these diaries.

Privatbesitz Maas

“We were a happy family, but there was also a lot of hidden sadness.”

Ton

My dear little Kees!

…. I have already written you that we have a small daughter, but whether the letters reach you, that is something one really does not know. Now Kees, I would almost be ready to come to you, but I will not make it over the border with your certificate. … I had to write a life report, send in a birth certificate and a political conduct certificate. Now I am curious how long it will take. … If I want to, they would bring me into the English Zone, but I would rather still stay here because I do not want to be in a camp with our little one. You see, here too everything is working out, one just always needs to have so much patience…. But what I will do, I need to borrow some money…. Mother also got no support for one quarter of a year, and I could not work because no one could get a job. Since you have been gone, I have been to the cinema only once. But Kees, once we are together again, then we will make up for everything. … Warmest greetings and many kisses from your little wife, who loves you very much and thinks of you always. Give my warmest regards to your parents and siblings. I will soon get to know them all.

Letter from Martha to Kees, 7 May 1946

Private property Maas

Dutch forced labourers in the German Reich

According to Nazi racist ideology, Dutch people as well as people from Denmark, Norway, and the Flemish part of Belgium were considered “members of Germanic peoples”. Forced labourers from these countries had greater freedom of movement and better opportunities to communicate with Germans, especially in comparison to Eastern European forced labourers. In some cases, they were deployed in companies as skilled labour. Contact with the German population was undesirable, but not forbidden. However, as with all other prisoners of war, interactions with Dutch prisoners of war were considered “forbidden contact”.

Erika with Ton, 1959

Erika and Ton recall having had a happy family life, although their family was different from others.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

Growing up in the Netherlands

Martha knew that life would be difficult for her as a German in post-war Dutch society. Nevertheless, she decided to live there with Kees and her children. Erika remembers her mother talking to the teachers when they expressed their anger towards Germans in class. Martha was worried that this anger could affect Erika. Martha spoke only once to her children about her experiences in the war, shortly before her death. Although Kees talked to friends about his time as a forced labourer, he told his children very little. Today, Erika and Ton regret not having asked their parents about their story. Ton’s daughter, however, was interested in the family’s history from an early age. She interviewed her grandfather Kees, thus preserving his stories for the family.

Interview

Erika van Santen, born 25 March 1946

Ton Maas, born 26 July 1956

Erika's and Ton's story

Erika and Ton grew up in Eindhoven in the Netherlands. However, a lot of German was spoken and sung at home because their mother was German. The siblings knew that their parents had met in Berlin during the Second World War, but this was rarely discussed in the family. It was important to their mother Martha that her children went to university, as she herself had not been able to do so during the war. Erika studied primary school education. She married her childhood friend Bram van Santen and moved with him to Capelle aan den IJssel, where they started a family. Her brother Ton, ten years younger, first studied astronomy and later business administration. He moved to Mierlo near Eindhoven with his wife Ine van Vijfeijken and their children. When he was 40 years old, he lost his ability to work due to health reasons. In 2016, he began intensively researching the history of his family. In the estate of their father Kees Maas, the siblings found diaries from his time as a forced labourer in Germany, as well as letters from Kees to his parents and from Martha to Kees. Based on these documents, Ton wrote a book about the history of his parents.

“And there was such a tension in our home, I didn’t know what it was, but I felt it.”

Erika

The Maas family, October 1956

Kees and Martha Maas with their three children Peter (left), Erika, and Ton. Peter died in 2011 at

age 61.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

The story of the parents

Born in the Netherlands in 1923, Kees Maas was transported to The German Reich in 1943 as a forced labourer, where he had to work at Telefunken in Berlin. He met 25-year-old German Martha Kopka at the doctor’s when they both wanted to take sick leave, even though they were not ill. They spent the day together and fell in love. When Martha was transferred to Reichenbach, now Dzierżoniów in Poland, they met secretly in Berlin and Reichenbach. With the help of friends and a fake travel permit, Kees even visited Martha in her home village of Alt Hammer (Kuźnica Katowska), southeast of Breslau (Wrocław) in what is now Poland. After the end of the war, they reunited in Ichstedt in Thuringia. Martha became pregnant and they married. Kees returned to the Netherlands and Martha and her daughter Erika were able to join him in 1947.

Martha and Kees on the day of their engagement in Berlin in front of bomb debris, July 1944

The city was the target of Allied air raids, especially in the last three years of the war.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

Birth certificate of Erika van Santen, 28 March 1946

Erika was born in Artern,Thuringia, in 1946. In late 1947, Martha Maas was allowed to leave the Soviet occupation zone with her daughter. She followed her husband Kees to the Netherlands, where Peter and Ton were born.

Private property van Santen

The diary of Kees Maas for the year 1945

Kees recorded observations, encounters, experiences, and feelings during his time as a forced labourer in the German Reich in several diaries. His first encounter with Martha is also recorded in these diaries.

Privatbesitz Maas

“We were a happy family, but there was also a lot of hidden sadness.”

Ton

My dear little Kees!

…. I have already written you that we have a small daughter, but whether the letters reach you, that is something one really does not know. Now Kees, I would almost be ready to come to you, but I will not make it over the border with your certificate. … I had to write a life report, send in a birth certificate and a political conduct certificate. Now I am curious how long it will take. … If I want to, they would bring me into the English Zone, but I would rather still stay here because I do not want to be in a camp with our little one. You see, here too everything is working out, one just always needs to have so much patience…. But what I will do, I need to borrow some money…. Mother also got no support for one quarter of a year, and I could not work because no one could get a job. Since you have been gone, I have been to the cinema only once. But Kees, once we are together again, then we will make up for everything. … Warmest greetings and many kisses from your little wife, who loves you very much and thinks of you always. Give my warmest regards to your parents and siblings. I will soon get to know them all.

Letter from Martha to Kees, 7 May 1946

Private property Maas

Dutch forced labourers in the German Reich

According to Nazi racist ideology, Dutch people as well as people from Denmark, Norway, and the Flemish part of Belgium were considered “members of Germanic peoples”. Forced labourers from these countries had greater freedom of movement and better opportunities to communicate with Germans, especially in comparison to Eastern European forced labourers. In some cases, they were deployed in companies as skilled labour. Contact with the German population was undesirable, but not forbidden. However, as with all other prisoners of war, interactions with Dutch prisoners of war were considered “forbidden contact”.

Erika with Ton, 1959

Erika and Ton recall having had a happy family life, although their family was different from others.

Photo: unknown. Private property Maas

Growing up in the Netherlands

Martha knew that life would be difficult for her as a German in post-war Dutch society. Nevertheless, she decided to live there with Kees and her children. Erika remembers her mother talking to the teachers when they expressed their anger towards Germans in class. Martha was worried that this anger could affect Erika. Martha spoke only once to her children about her experiences in the war, shortly before her death. Although Kees talked to friends about his time as a forced labourer, he told his children very little. Today, Erika and Ton regret not having asked their parents about their story. Ton’s daughter, however, was interested in the family’s history from an early age. She interviewed her grandfather Kees, thus preserving his stories for the family.

Interview

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.