Prisoners of war and forced labourers in Nazi society

Arrival of Yugoslav and French prisoners of war at Bremervörde railway station in the northwest of today’s Lower Saxony, undated

Photo: Friedrich Rugen. Sandbostel Camp Memorial

The transfer of power to the National Socialist German Labour Party (NSDAP) under Adolf Hitler in 1933 marked the beginning of the establishment of a dictatorship in the German Reich. The pseudo-scientific assertion that there were human “races” and the associated denigration of so-called inferior peoples did not originate in the Nazi era, but it formed the ideological basis for the disenfranchisement and murder of people on a massive scale. The Nazi state began to persecute those who did not conform to an ideologically defined German “Volksgemeinschaft” (ethnic community). These targeted groups included Jews, Sinti, and Roma, as well as queer and disabled people and those stigmatised as “asocial”.

The SA and SS set up the first concentration camps as early as 1933, in which they interned mainly political opponents and later also other persecutees and forced them to work. The Nazis launched their war of aggression and extermination with the German Wehrmacht’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; the Second World War began, and with it the deportation of prisoners of war and forced labourers. Starting in 1941, the SS set up extermination camps, above all in occupied Poland, where Jews in particular were systematically murdered.

Propaganda poster “Protect mother and child, the most precious asset of your people!”, between 1934 and 1945

The National Socialist People’s Welfare Organisation (NSV) set up an aid organisation to support pregnant women and young mothers who were considered “Aryan”.

Federal Archives

The National Socialist image of the family

The Nazi regime reinforced the gender-specific distribution of roles and assigned German women the function of housewife and mother. They were expected to have as many children as possible and raise them in accordance with Nazi ideology. To achieve this, the regime resorted to measures such as providing family support, but this only benefited families who were considered part of the “ethnic community”.

During the course of the Second World War, more and more men were drafted into the Wehrmacht. This led to a labour shortage in the German Reich. Therefore, contrary to their role as ascribed in the propaganda, German women—preferably those who were unmarried and childless—were deployed as workers.

Soviet forced labourers in front of their barracks in Kornwestheim in the District of Ludwigsburg, February 1942

The women wear a patch labelled “OST” (East) on their clothing. This was mandatory for forced labourers from the Soviet Union to make them easy to recognise and as a sign of exclusion.

Photo: unknown. Memorial Research and Education Centre, Moscow

“The hierarchy on a farm … is clearly demarcated. First comes the farmer and his family, then the dog, then the German employees; way after that came the prisoners of war and finally the Poles and Russians.”

Valentin Vanderbeke, former Belgian prisoner of war, 1986

Prisoners of war and forced labourers

In total, around 4.6 million prisoners of war and 8.5 million foreign forced labourers were deployed for work in the German Reich. They were visible throughout society and had to work in agriculture, manual trades, industry, logistics, and as domestic servants, among other things. Some civilians in the German-occupied countries were persuaded with false promises to “voluntarily” come to the German Reich to work. However, the majority were coercively transported for forced labour. The Nazis also deployed prisoners of war from opposing armies, who were allowed to be used for labour under the 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.

French colonial soldiers in Stalag III A Luckenwalde in Brandenburg, 1940

Tens of thousands of colonial soldiers of African and Asian origin also became German prisoners of war. To prevent their contact with the population, they were not deployed to work in the German Reich.

Photo: unknown. Luckenwalde Heimatmuseum

Racist hierarchisation of foreign workers

Contrary to the provisions of the International Geneva Convention, the Wehrmacht discriminated in its handling of prisoners of war. How they were treated was determined not only by National Socialist racial ideology but also by foreign policy factors and the course of the war. Eastern European prisoners of war had to live and work under worse conditions than their Western European counterparts.

Polish and Soviet forced labourers were interned in secure camps often located away from urban areas. They were only allowed to leave for work. Western European forced labourers were sometimes housed in barracks or buildings in the villages and towns. Prisoners of war and forced agricultural labourers often lived on farms and therefore had greater freedom of movement. Western European prisoners of war were sometimes allowed to leave their accommodations on their own.

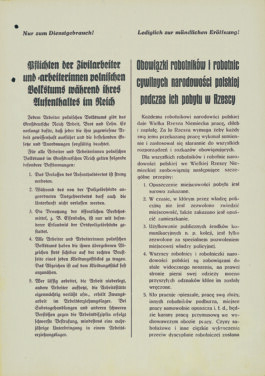

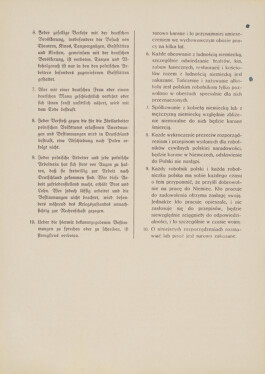

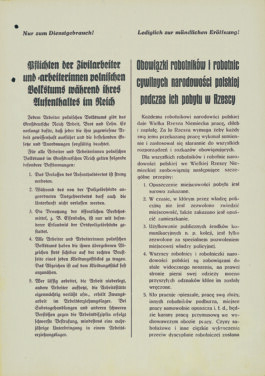

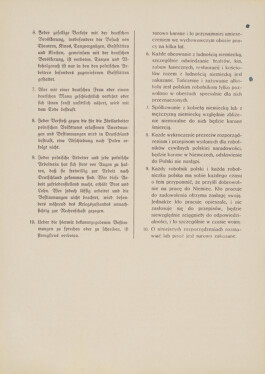

Handout on the “Poland Decrees”, undated

On 8 March 1940, six months after the German attack on Poland, the decrees created special rights to discriminate against and economically exploit Polish forced labourers.

Lower Austrian Provincial Archives

Prisoners of war and forced labourers in Nazi society

Arrival of Yugoslav and French prisoners of war at Bremervörde railway station in the northwest of today’s Lower Saxony, undated

Photo: Friedrich Rugen. Sandbostel Camp Memorial

The transfer of power to the National Socialist German Labour Party (NSDAP) under Adolf Hitler in 1933 marked the beginning of the establishment of a dictatorship in the German Reich. The pseudo-scientific assertion that there were human “races” and the associated denigration of so-called inferior peoples did not originate in the Nazi era, but it formed the ideological basis for the disenfranchisement and murder of people on a massive scale. The Nazi state began to persecute those who did not conform to an ideologically defined German “Volksgemeinschaft” (ethnic community). These targeted groups included Jews, Sinti, and Roma, as well as queer and disabled people and those stigmatised as “asocial”.

The SA and SS set up the first concentration camps as early as 1933, in which they interned mainly political opponents and later also other persecutees and forced them to work. The Nazis launched their war of aggression and extermination with the German Wehrmacht’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; the Second World War began, and with it the deportation of prisoners of war and forced labourers. Starting in 1941, the SS set up extermination camps, above all in occupied Poland, where Jews in particular were systematically murdered.

Propagandaplakat »Schütze Mutter und Kind, das kostbarste Gut deines Volkes!«, zwischen 1934 und 1945

Die Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (NSV) richtete ein Hilfswerk zur Unterstützung als »arisch« geltender Schwangerer und junger Mütter ein.

Bundesarchiv

The National Socialist image of the family

The Nazi regime reinforced the gender-specific distribution of roles and assigned German women the function of housewife and mother. They were expected to have as many children as possible and raise them in accordance with Nazi ideology. To achieve this, the regime resorted to measures such as providing family support, but this only benefited families who were considered part of the “ethnic community”.

During the course of the Second World War, more and more men were drafted into the Wehrmacht. This led to a labour shortage in the German Reich. Therefore, contrary to their role as ascribed in the propaganda, German women—preferably those who were unmarried and childless—were deployed as workers.

Soviet forced labourers in front of their barracks in Kornwestheim in the District of Ludwigsburg, February 1942

The women wear a patch labelled “OST” (East) on their clothing. This was mandatory for forced labourers from the Soviet Union to make them easy to recognise and as a sign of exclusion.

Photo: unknown. Memorial Research and Education Centre, Moscow

“The hierarchy on a farm … is clearly demarcated. First comes the farmer and his family, then the dog, then the German employees; way after that came the prisoners of war and finally the Poles and Russians.”

Valentin Vanderbeke, former Belgian prisoner of war, 1986

Prisoners of war and forced labourers

In total, around 4.6 million prisoners of war and 8.5 million foreign forced labourers were deployed for work in the German Reich. They were visible throughout society and had to work in agriculture, manual trades, industry, logistics, and as domestic servants, among other things. Some civilians in the German-occupied countries were persuaded with false promises to “voluntarily” come to the German Reich to work. However, the majority were coercively transported for forced labour. The Nazis also deployed prisoners of war from opposing armies, who were allowed to be used for labour under the 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.

French colonial soldiers in Stalag III A Luckenwalde in Brandenburg, 1940

Tens of thousands of colonial soldiers of African and Asian origin also became German prisoners of war. To prevent their contact with the population, they were not deployed to work in the German Reich.

Photo: unknown. Luckenwalde Heimatmuseum

Racist hierarchisation of foreign workers

Contrary to the provisions of the International Geneva Convention, the Wehrmacht discriminated in its handling of prisoners of war. How they were treated was determined not only by National Socialist racial ideology but also by foreign policy factors and the course of the war. Eastern European prisoners of war had to live and work under worse conditions than their Western European counterparts.

Polish and Soviet forced labourers were interned in secure camps often located away from urban areas. They were only allowed to leave for work. Western European forced labourers were sometimes housed in barracks or buildings in the villages and towns. Prisoners of war and forced agricultural labourers often lived on farms and therefore had greater freedom of movement. Western European prisoners of war were sometimes allowed to leave their accommodations on their own.

Handout on the “Poland Decrees”, undated

On 8 March 1940, six months after the German attack on Poland, the decrees created special rights to discriminate against and economically exploit Polish forced labourers.

Lower Austrian Provincial Archives

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.