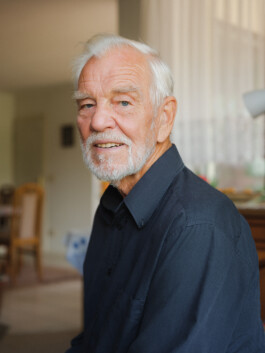

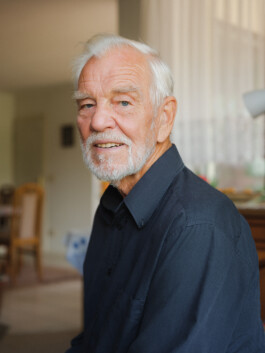

Heinz-Dieter Nehls, born 4 September 1944

Heinz-Dieter's story

On Father’s Day in 2010, Heinz-Dieter Nehls’s daughter surprised her father with a special gift: he was asked to answer various questions about his life in a memory album and thus pass on the family history to his children. But he was unable to answer the very first question: “When and where were you born?” Heinz-Dieter had known about his adoption since he was 18 years old and that his birth name was Volgmann. He was told he had been found in front of a church. However, his documents contained different dates and places of birth. As he loved his adoptive parents very much, he decided not to look for his biological parents. He lived in the GDR. And when, as a young man, he applied to apprentice as a fire investigation officer, he was rejected because his birth mother lived in West Germany. But apart from that, for a long time his origin was not an issue for him. This did not change until Father’s Day in 2010. His son-in-law entered the search term “Heinz-Dieter Volgmann” in an internet search engine. The results included a search notice: Heinz-Dieter’s birth mother, Herta Wiersma, was looking for him. Two weeks later, they met again for the first time in more than 60 years.

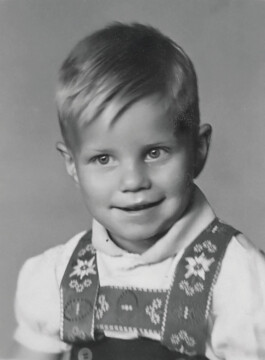

Heinz-Dieter Nehls at the age of five, 1949

Herta Wiersma inserted this photo into her search notice on the internet. It was the only one that Heinz-Dieter’s adoptive parents had sent her. He recognised himself immediately as he had a print of the picture.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Heinz-Dieter Nehls at his workplace in Schwerin, 1990s

Heinz-Dieter spent almost his entire working life in a cable factory, where, among other things, he was responsible for fire safety. In his spare time, he served in the volunteer fire brigade.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Herta Wiersma in her home village of Medow near Anklam in Western Pomerania, ca. 1940

Without realising it, Herta and her son Heinz-Dieter shared a love of dogs. It was only when they met again in 2010 that they realised they had something in common.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

The story of the parents

Herta Wiersma grew up as the daughter of a Communist and Nazi opponent who was arrested in 1938 and later murdered in Mauthausen Concentration Camp. She and her mother were conscripted to work on the farm of a Nazi family. It was there that Herta and the Polish forced labourer Henryk Piechal fell in love. When Herta became pregnant, Protestant nuns took her in and enabled her to give birth in secret. Shortly before the end of the Second World War, Herta and Henryk were travelling to Poland together. On the way, Herta was recognised as German by Soviet soldiers and raped. She turned back and Henryk went to Warsaw alone. Herta left the Soviet occupation zone in 1945, heading for the Bergisches Land region near Cologne. She wanted to collect Heinz-Dieter later, but it was not possible and she lost contact with his subsequent adoptive parents.

Henryk Piechal in Warsaw, ca. 1975

Heinz-Dieter’s biological father started a family in Poland after the war. He was in regular contact with Herta Wiersma until his death at the end of the 1970s. He also sent her this photo of himself.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Forced labour in agriculture

During the Second World War, prisoners of war and forced labourers were first deployed in large numbers in agriculture. By the end of the war, they were doing around half of the work in the sector. In agriculture, unlike in industrial operations, for example, foreign labourers could not be kept from coming into contact with each other and with employers and German employees. The civilian forced labourers, in particular, were usually housed directly on the farms, which made continuous monitoring by the authorities impossible. On the one hand, prisoners of war and forced labourers were often exposed to the arbitrariness of their employers. On the other hand, however, there were also certain freedoms such as friendly contacts, which could develop into forbidden relationships.

Interview

“She must have always been looking for me in her heart.”

Herta Wiersma and Heinz-Dieter Nehls in Engelskirchen near Cologne, 19 June 2010

Norddeutscher Rundfunk not only supported Herta Wiersma in her search for her son, but also followed their first reunion on camera. Three years after this meeting, Herta passed away.

Photo: Thomas Balzer. Norddeutscher Rundfunk

A mother searches for her son

After the Second World War, Herta Wiersma married a man who forbade her to search for Heinz-Dieter. She only began her research after their divorce in 1980. Her four younger sons—Heinz-Dieter’s half-brothers—and, above all, a family friend supported her in her endeavours. The friend wrote to more than 30 archives, registry offices, and tracing services on Herta’s behalf. Today, Heinz-Dieter assumes that the authorities in the GDR prevented a reunion. In 2007, Herta was interviewed by a journalist for a television programme about her father’s history as a victim of National Socialism. In passing, she also talked about the search for her son. The journalist promised Herta that he would help her and published her search notice on the internet. This is how Herta found her son again three years later.

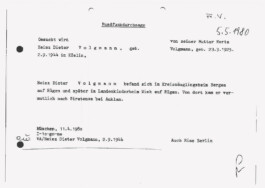

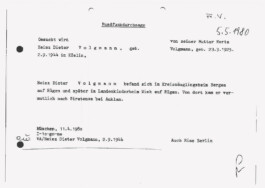

Text of a radio announcement regarding the search for Heinz-Dieter Nehls, 1980

For Herta Wiersma, who also used her birth name Volgmann in her search, it was difficult to make enquiries in the GDR. However, the West Berlin radio station RIAS could be received in large parts of the GDR.

Private property Nehls

Heinz-Dieter Nehls, born 4 September 1944

Heinz-Dieter's story

On Father’s Day in 2010, Heinz-Dieter Nehls’s daughter surprised her father with a special gift: he was asked to answer various questions about his life in a memory album and thus pass on the family history to his children. But he was unable to answer the very first question: “When and where were you born?” Heinz-Dieter had known about his adoption since he was 18 years old and that his birth name was Volgmann. He was told he had been found in front of a church. However, his documents contained different dates and places of birth. As he loved his adoptive parents very much, he decided not to look for his biological parents. He lived in the GDR. And when, as a young man, he applied to apprentice as a fire investigation officer, he was rejected because his birth mother lived in West Germany. But apart from that, for a long time his origin was not an issue for him. This did not change until Father’s Day in 2010. His son-in-law entered the search term “Heinz-Dieter Volgmann” in an internet search engine. The results included a search notice: Heinz-Dieter’s birth mother, Herta Wiersma, was looking for him. Two weeks later, they met again for the first time in more than 60 years.

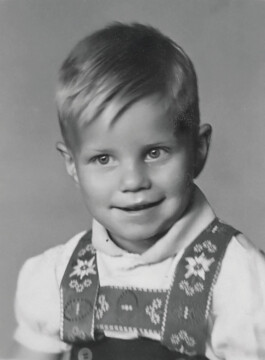

Heinz-Dieter Nehls at the age of five, 1949

Herta Wiersma inserted this photo into her search notice on the internet. It was the only one that Heinz-Dieter’s adoptive parents had sent her. He recognised himself immediately as he had a print of the picture.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Heinz-Dieter Nehls at his workplace in Schwerin, 1990s

Heinz-Dieter spent almost his entire working life in a cable factory, where, among other things, he was responsible for fire safety. In his spare time, he served in the volunteer fire brigade.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Herta Wiersma in her home village of Medow near Anklam in Western Pomerania, ca. 1940

Without realising it, Herta and her son Heinz-Dieter shared a love of dogs. It was only when they met again in 2010 that they realised they had something in common.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

The story of the parents

Herta Wiersma grew up as the daughter of a Communist and Nazi opponent who was arrested in 1938 and later murdered in Mauthausen Concentration Camp. She and her mother were conscripted to work on the farm of a Nazi family. It was there that Herta and the Polish forced labourer Henryk Piechal fell in love. When Herta became pregnant, Protestant nuns took her in and enabled her to give birth in secret. Shortly before the end of the Second World War, Herta and Henryk were travelling to Poland together. On the way, Herta was recognised as German by Soviet soldiers and raped. She turned back and Henryk went to Warsaw alone. Herta left the Soviet occupation zone in 1945, heading for the Bergisches Land region near Cologne. She wanted to collect Heinz-Dieter later, but it was not possible and she lost contact with his subsequent adoptive parents.

Henryk Piechal in Warsaw, ca. 1975

Heinz-Dieter’s biological father started a family in Poland after the war. He was in regular contact with Herta Wiersma until his death at the end of the 1970s. He also sent her this photo of himself.

Photo: unknown. Private property Nehls

Forced labour in agriculture

During the Second World War, prisoners of war and forced labourers were first deployed in large numbers in agriculture. By the end of the war, they were doing around half of the work in the sector. In agriculture, unlike in industrial operations, for example, foreign labourers could not be kept from coming into contact with each other and with employers and German employees. The civilian forced labourers, in particular, were usually housed directly on the farms, which made continuous monitoring by the authorities impossible. On the one hand, prisoners of war and forced labourers were often exposed to the arbitrariness of their employers. On the other hand, however, there were also certain freedoms such as friendly contacts, which could develop into forbidden relationships.

“She must have always been looking for me in her heart.”

Interview

Herta Wiersma and Heinz-Dieter Nehls in Engelskirchen near Cologne, 19 June 2010

Norddeutscher Rundfunk not only supported Herta Wiersma in her search for her son, but also followed their first reunion on camera. Three years after this meeting, Herta passed away.

Photo: Thomas Balzer. Norddeutscher Rundfunk

A mother searches for her son

After the Second World War, Herta Wiersma married a man who forbade her to search for Heinz-Dieter. She only began her research after their divorce in 1980. Her four younger sons—Heinz-Dieter’s half-brothers—and, above all, a family friend supported her in her endeavours. The friend wrote to more than 30 archives, registry offices, and tracing services on Herta’s behalf. Today, Heinz-Dieter assumes that the authorities in the GDR prevented a reunion. In 2007, Herta was interviewed by a journalist for a television programme about her father’s history as a victim of National Socialism. In passing, she also talked about the search for her son. The journalist promised Herta that he would help her and published her search notice on the internet. This is how Herta found her son again three years later.

Text of a radio announcement regarding the search for Heinz-Dieter Nehls, 1980

For Herta Wiersma, who also used her birth name Volgmann in her search, it was difficult to make enquiries in the GDR. However, the West Berlin radio station RIAS could be received in large parts of the GDR.

Private property Nehls

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.