The unknown child

Stories that cannot be told here

Many of the life stories of children from forbidden relationships cannot be told. There are many reasons for this. For example, how many of these children there were is still unknown. Their number cannot be determined or even estimated. For fear of persecution, mothers would also try to conceal their pregnancy or disclaim their partner and pretend their child was from another man. Most of these cases cannot be reconstructed. Some of these children still do not know that they were born out of a forbidden relationship. Others who know do not want to talk about it publicly. Moreover, the call for participation in the “nevertheless here!” project will not have reached many of the children concerned. This is particularly true for those who never grew up or do not live in Germany.

Also remaining untold are the stories of the children who did not survive. But for some of these children there still are traces that can be followed.

Annemarie Hofinger, daughter of an Austrian woman and a Polish forced labourer, 1943

Annemarie’s parents, Aloisia Hofinger and Josef Gowdek, were denounced in 1942 because of their relationship. Aloisia was sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, and Josef was hanged. After her imprisonment, Aloisia never saw her daughter again, who died of diphtheria in October 1943.

Photo: unknown. Private property Elfriede Schober

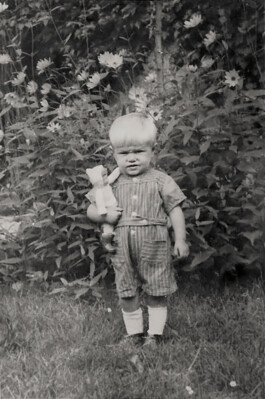

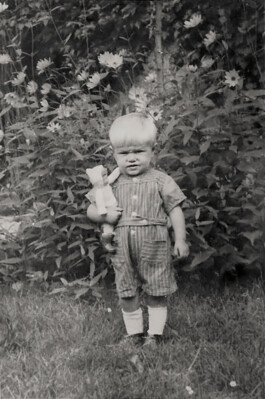

Helmut, presumably in 1947 or 1948

The German Engelhardt family took in Helmut, the child of a German woman and a French forced labourer, in 1944. Helmut was repatriated to France around 1949. Today, the grandson of Helmut’s adoptive sister, René Vincze, is trying to find and contact him.

Photo: unknown. Private property René Vincze

Memorial stone for Annemarie and Wilfried Gerken in the Iselersheim District of Bremervörder, 2023

As a child, Wilfried was sent to live with relatives in the United States. When he learned from the Iselersheim Local History Association in 1990 that his mother Annemarie Gerken and his father, the Polish forced labourer Stefan Szablewski, had a forbidden relationship, he reacted dismissively.

Photo: Hermann Röttjer. Private property Röttjer

Life without the story of the parents

It can be assumed that most children born from a forbidden relationship are unaware of this. Similarly, adopted children often did not find out who their biological parents were. For some, the relationship with their adoptive parents was so close that they did not want to search for their biological parents. In families where the children grew up with a biological parent, it often took a great deal of courage and vigour to break the silence in the family. In many cases, only the first name of the parent who had been a prisoner of war or forced labourer was passed down in the families. Other children were not even told who their second biological parent was. Some only began to search in old age, when most of those who could have provided information had already passed away. Not all of them were able to carry out research in archives with the little information they nonetheless obtained.

“We are looking for our German brother/cousin!

My uncle, Henricus Theodorus CORVERS, was a forced labourer during the Second World War at the Reich Post Office in Leipzig.

…

We have recently found out that he also had a son with a German woman, born between 1943 and 1945. The name of the child is presumably Heinrich. Unfortunately, we do not know the name of the woman.

We would like to get in contact with him; he still has four siblings!”

Search appeal in Leipzig by the Dutch Covers family, 2018

The relatives of a Dutch forced labourer who was deployed in Leipzig during the Second World War are looking for their half-brother or cousin, who is presumably called “Heinrich”. The search has so far been unsuccessful.

Privatbesitz Corvers

“My mother feels shame about her origins, which were taboo in the family. Even today, she hardly talks about it.”

Sascha Kirchner, grandson of a German woman and an Italian military internee

Shame and silence

For quite a few children born from forbidden relationships, their own history is such a burden that they are not prepared to talk about it. For some, the pain of not having learned who their biological parents are is too great. The memory of being marginalised and devalued because of their origins can also be too distressing. Others only talk about their parents’ story with friends or within their family and do not want to tell it publicly.

Foreign children care centres

During the first years of the war, pregnant forced labourers from Poland and the Soviet Union would be sent back to their home countries. Starting in 1943, however, they had to remain in the German Reich and frequently had to return to work shortly after giving birth. The children would be forcibly adopted or taken to homes set up by the Nazi Party, so-called Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätten (foreign children care centres). They were often located in barracks or stables, and the children were deliberately neglected. Due to inadequate hygiene and nutrition as well as the withholding of medical care, the mortality rate in these centres was as high as 90%. In total, at least 50,000 children did not survive these homes. How many of these children were from forbidden relationships is unknown.

“Foreign children care home“ of the Volkswagen factory in Rühen in the District of Gifhorn, 1945

The home was one of three “Ausländerkinder-Pflegeheime” (foreign children care homes) for the children of Eastern European forced labourers at the Volkswagen factory based in the “city of the KdF car”, now Wolfsburg. Between 350 and 400 children died in these three homes as a result of deliberate neglect.

Photo: unknown. The National Archives, London

The unknown child

Stories that cannot be told here

Many of the life stories of children from forbidden relationships cannot be told. There are many reasons for this. For example, how many of these children there were is still unknown. Their number cannot be determined or even estimated. For fear of persecution, mothers would also try to conceal their pregnancy or disclaim their partner and pretend their child was from another man. Most of these cases cannot be reconstructed. Some of these children still do not know that they were born out of a forbidden relationship. Others who know do not want to talk about it publicly. Moreover, the call for participation in the “nevertheless here!” project will not have reached many of the children concerned. This is particularly true for those who never grew up or do not live in Germany.

Also remaining untold are the stories of the children who did not survive. But for some of these children there still are traces that can be followed.

Annemarie Hofinger, daughter of an Austrian woman and a Polish forced labourer, 1943

Annemarie’s parents, Aloisia Hofinger and Josef Gowdek, were denounced in 1942 because of their relationship. Aloisia was sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, and Josef was hanged. After her imprisonment, Aloisia never saw her daughter again, who died of diphtheria in October 1943.

Photo: unknown. Private property Elfriede Schober

Helmut, presumably in 1947 or 1948

The German Engelhardt family took in Helmut, the child of a German woman and a French forced labourer, in 1944. Helmut was repatriated to France around 1949. Today, the grandson of Helmut’s adoptive sister, René Vincze, is trying to find and contact him.

Photo: unknown. Private property René Vincze

Memorial stone for Annemarie and Wilfried Gerken in the Iselersheim District of Bremervörder, 2023

As a child, Wilfried was sent to live with relatives in the United States. When he learned from the Iselersheim Local History Association in 1990 that his mother Annemarie Gerken and his father, the Polish forced labourer Stefan Szablewski, had a forbidden relationship, he reacted dismissively.

Photo: Hermann Röttjer. Private property Röttjer

Life without the story of the parents

It can be assumed that most children born from a forbidden relationship are unaware of this. Similarly, adopted children often did not find out who their biological parents were. For some, the relationship with their adoptive parents was so close that they did not want to search for their biological parents. In families where the children grew up with a biological parent, it often took a great deal of courage and vigour to break the silence in the family. In many cases, only the first name of the parent who had been a prisoner of war or forced labourer was passed down in the families. Other children were not even told who their second biological parent was. Some only began to search in old age, when most of those who could have provided information had already passed away. Not all of them were able to carry out research in archives with the little information they nonetheless obtained.

“We are looking for our German brother/cousin!

My uncle, Henricus Theodorus CORVERS, was a forced labourer during the Second World War at the Reich Post Office in Leipzig.

…

We have recently found out that he also had a son with a German woman, born between 1943 and 1945. The name of the child is presumably Heinrich. Unfortunately, we do not know the name of the woman.

We would like to get in contact with him; he still has four siblings!”

Search appeal in Leipzig by the Dutch Covers family, 2018

The relatives of a Dutch forced labourer who was deployed in Leipzig during the Second World War are looking for their half-brother or cousin, who is presumably called “Heinrich”. The search has so far been unsuccessful.

Privatbesitz Corvers

“My mother feels shame about her origins, which were taboo in the family. Even today, she hardly talks about it.”

Sascha Kirchner, grandson of a German woman and an Italian military internee

Shame and silence

For quite a few children born from forbidden relationships, their own history is such a burden that they are not prepared to talk about it. For some, the pain of not having learned who their biological parents are is too great. The memory of being marginalised and devalued because of their origins can also be too distressing. Others only talk about their parents’ story with friends or within their family and do not want to tell it publicly.

Foreign children care centres

During the first years of the war, pregnant forced labourers from Poland and the Soviet Union would be sent back to their home countries. Starting in 1943, however, they had to remain in the German Reich and frequently had to return to work shortly after giving birth. The children would be forcibly adopted or taken to homes set up by the Nazi Party, so-called Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätten (foreign children care centres). They were often located in barracks or stables, and the children were deliberately neglected. Due to inadequate hygiene and nutrition as well as the withholding of medical care, the mortality rate in these centres was as high as 90%. In total, at least 50,000 children did not survive these homes. How many of these children were from forbidden relationships is unknown.

“Foreign children care home“ of the Volkswagen factory in Rühen in the District of Gifhorn, 1945

The home was one of three “Ausländerkinder-Pflegeheime” (foreign children care homes) for the children of Eastern European forced labourers at the Volkswagen factory based in the “city of the KdF car”, now Wolfsburg. Between 350 and 400 children died in these three homes as a result of deliberate neglect.

Photo: unknown. The National Archives, London

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.