Family

“Mum, now you can see your eldest.”

Friedrich Buhlrich at the grave of his biological mother, 2004

Friedrich Buhlrich grew up with adoptive parents. He only found out at age 20 that he was the child of a German woman and a former Polish forced labourer.

Many children from forbidden relationships did not know for a long time that one of their parents had been a prisoner of war or forced labourer. Those of them who grew up with their German mothers often wondered who and where their father was. Mothers frequently remained silent and left questions unanswered. This silence was often due not only to shame but also to concerns about social marginalisation. Other children grew up with adoptive parents and in some cases only found out very late. They too described how they would have liked to have known who their biological parents were earlier.

Some parents who were separated during the turmoil of war managed to find each other again in the post-war period. If they then decided to live together as a family, they were ostracised in many cases.

If families remained in Germany, the previously foreign parents were often subjected to racist hostility, as were their children. If such families went to the country of origin of the former forced labourer or prisoner of war, they frequently experienced ostracism, as German origins were associated with Nazi crimes. In all cases, the hostility had a lasting effect on the children.

Anna Maria and Henryk Wrzesinski, undated

Anna Maria and the Polish forced labourer Henryk were denounced in Wolfertschwenden, Bavaria, when it was discovered that they were expecting a child. After the war, they both returned to Wolfertschwenden and raised their child together.

Photo: unknown. Wißner-Verlag, Augsburg

Elisabeth Schneider with her son Hans, 1943 or 1944

To this day, Hans Schneider still doesn’t know who his father is. His mother only told him that his father was French and had worked at the post office in Lille before the war.

Photo: unknown. Private property Schneider

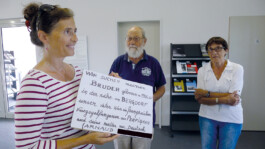

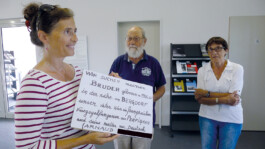

A French family at the Sandbostel Camp Memorial, 2015

With this sign in the pedestrian zone of Hamburg-Bergedorf, the daughter (right) of a former French prisoner of war and a German woman tried to obtain information about her unknown German half-brother.

Photo: Andreas Ehresmann. Sandbostel Camp Memorial

Search

Many children from forbidden relationships only started looking for their unknown parent or biological parents after their known parent or foster parents had died. Some had long suspected or known something but never investigated out of consideration for their social parents or relatives.

Many searched for decades, writing to archives, looking through telephone directories and address books, travelling to places connected with their parents’ history, and publishing search notices in newspapers. Such searches were not always successful, especially if neither the name nor the date of birth of the person being sought was known. If the parents had been denounced and convicted during the war, surviving court records might contain information.

Search queries and answers

Many children from forbidden relationships have written to archives, among other places, when searching for their biological parents. Some of their search requests and the answers they received can be viewed here.

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit (2nd from left) with his family in Greece, 2001

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit, the son of a German and a Greek forced labourer, succeeded in finding his family in Greece in 1997. To this day, he spends several months every year with his Greek relatives.

Photo: unknown. Private property Kurbjuweit

New families

The former prisoners of war or forced labourers that the children from forbidden relationships were looking for might already have been married before they were captured or brought to Germany; they might also have started a new family after their return. The searching children therefore had to decide whether they wanted to make contact with this new part of their family. Some decided against it. They were afraid of rejection or worried about introducing conflict to the family. Some, however, established contact, and a few managed to develop a connection with their biological parents or other relatives. Others, however, experienced rejection from

the new part of their family.

Brian Gerken at the grave of his grandfather Stefan Szablewski, who was executed in 1941, in Bremerhaven, 2021

Brian’s father, Wilfried Gerken, had been sent to the United States alone as a child. Not until his father died did Brian learn that his paternal grandparents were a German and a Polish forced labourer. His grandmother Annemarie was murdered in Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

Photo: Hermann Röttjer. Private property Röttjer

Subsequent generations

The persecution of the parents and the marginalisation experienced by children from forbidden relationships in the post-war period continue to have an impact on the third and fourth generation. In some cases, their own history was so painful for the children of the persecuted that they did not talk about it. Often it was the grandchildren or great-grandchildren who first began researching the family history and looking for family members.

Even in cases where the now elderly children from forbidden relationships research their own history, it is often grandchildren and great-grandchildren who support them, accompany them to interviews with contemporary witnesses, and carry the story forward.

Family

“Mum, now you can see your eldest.”

Friedrich Buhlrich at the grave of his biological mother, 2004

Friedrich Buhlrich grew up with adoptive parents. He only found out at age 20 that he was the child of a German woman and a former Polish forced labourer.

Many children from forbidden relationships did not know for a long time that one of their parents had been a prisoner of war or forced labourer. Those of them who grew up with their German mothers often wondered who and where their father was. Mothers frequently remained silent and left questions unanswered. This silence was often due not only to shame but also to concerns about social marginalisation. Other children grew up with adoptive parents and in some cases only found out very late. They too described how they would have liked to have known who their biological parents were earlier.

Some parents who were separated during the turmoil of war managed to find each other again in the post-war period. If they then decided to live together as a family, they were ostracised in many cases.

If families remained in Germany, the previously foreign parents were often subjected to racist hostility, as were their children. If such families went to the country of origin of the former forced labourer or prisoner of war, they frequently experienced ostracism, as German origins were associated with Nazi crimes. In all cases, the hostility had a lasting effect on the children.

Anna Maria and Henryk Wrzesinski, undated

Anna Maria and the Polish forced labourer Henryk were denounced in Wolfertschwenden, Bavaria, when it was discovered that they were expecting a child. After the war, they both returned to Wolfertschwenden and raised their child together.

Photo: unknown. Wißner-Verlag, Augsburg

Elisabeth Schneider with her son Hans, 1943 or 1944

To this day, Hans Schneider still doesn’t know who his father is. His mother only told him that his father was French and had worked at the post office in Lille before the war.

Photo: unknown. Private property Schneider

A French family at the Sandbostel Camp Memorial, 2015

With this sign in the pedestrian zone of Hamburg-Bergedorf, the daughter (right) of a former French prisoner of war and a German woman tried to obtain information about her unknown German half-brother.

Photo: Andreas Ehresmann. Sandbostel Camp Memorial

Search

Many children from forbidden relationships only started looking for their unknown parent or biological parents after their known parent or foster parents had died. Some had long suspected or known something but never investigated out of consideration for their social parents or relatives.

Many searched for decades, writing to archives, looking through telephone directories and address books, travelling to places connected with their parents’ history, and publishing search notices in newspapers. Such searches were not always successful, especially if neither the name nor the date of birth of the person being sought was known. If the parents had been denounced and convicted during the war, surviving court records might contain information.

Search queries and answers

Many children from forbidden relationships have written to archives, among other places, when searching for their biological parents. Some of their search requests and the answers they received can be viewed here.

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit (2nd from left) with his family in Greece, 2001

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit, the son of a German and a Greek forced labourer, succeeded in finding his family in Greece in 1997. To this day, he spends several months every year with his Greek relatives.

Photo: unknown. Private property Kurbjuweit

New families

The former prisoners of war or forced labourers that the children from forbidden relationships were looking for might already have been married before they were captured or brought to Germany; they might also have started a new family after their return. The searching children therefore had to decide whether they wanted to make contact with this new part of their family. Some decided against it. They were afraid of rejection or worried about introducing conflict to the family. Some, however, established contact, and a few managed to develop a connection with their biological parents or other relatives. Others, however, experienced rejection from

the new part of their family.

Brian Gerken at the grave of his grandfather Stefan Szablewski, who was executed in 1941, in Bremerhaven, 2021

Brian’s father, Wilfried Gerken, had been sent to the United States alone as a child. Not until his father died did Brian learn that his paternal grandparents were a German and a Polish forced labourer. His grandmother Annemarie was murdered in Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

Photo: Hermann Röttjer. Private property Röttjer

Subsequent generations

The persecution of the parents and the marginalisation experienced by children from forbidden relationships in the post-war period continue to have an impact on the third and fourth generation. In some cases, their own history was so painful for the children of the persecuted that they did not talk about it. Often it was the grandchildren or great-grandchildren who first began researching the family history and looking for family members.

Even in cases where the now elderly children from forbidden relationships research their own history, it is often grandchildren and great-grandchildren who support them, accompany them to interviews with contemporary witnesses, and carry the story forward.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.