Forbidden relationships

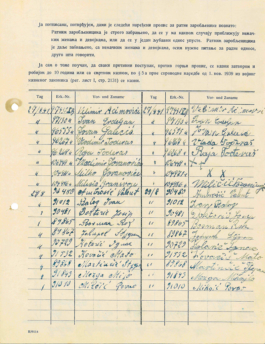

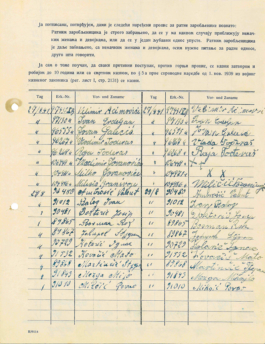

Advisory notice signed by Yugoslav prisoners of war, 22 August 1941

The prisoners of war were cautioned in Serbian that relationships with German women or girls were punishable by ten years in prison or death.

Stadtarchiv Eutin

Close contact between Germans and prisoners of war was forbidden for reasons of military and political security. Contact with forced labourers was generally undesirable, and contact with those stigmatised as “fremdvölkisch” (ethnically foreign) was also forbidden for racist reasons.

Under an initial ordinance issued as early as November 1939, “forbidden contact with prisoners of war” beyond communications necessary for work was punishable with imprisonment or Zuchthaus (penal servitude). Further regulations followed with the “Polen-Erlasse” (Polish Decrees) of 1940 and the “Ostarbeiter-Erlasse” (Eastern Workers Decrees) of 1942. Among other things, they made relationships and love affairs with Germans a severely punishable offence. In order to prevent male Western European forced labourers from having sexual contact with Germans, the Nazi regime started setting up brothels for them in 1939.These brothels only used women

considered “ethnically foreign” to perform the sexualised forced labour.

Despite the threats of punishment, there were numerous encounters, including sexual contact and love affairs. In many cases, offenders were denounced by people from their immediate environment, for example by work colleagues. The accused were subsequently often publicly humiliated and subjected to degrading interrogations.

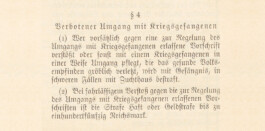

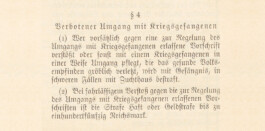

Ordinance Supplementing the Penal Provisions for the Protection of the Military Strength of the German People of 25 November 1939, extract

Germans were threatened with imprisonment or penal servitude for “illegal contact with prisoners of war”.

Berlin State Library

Forms of relationships

There were many different types of contact between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers. It might be an exchange of cigarettes or food or a friendly chat. This in turn could develop into a romantic relationship or sexual contact, whether in the context of a love affair or sex work. Not all sexual contact was consensual; it ranged from sexual bartering to psychological pressure in the workplace and to rape. In some cases, Germans also helped prisoners of war or forced labourers to escape by giving them civilian clothes or forged documents or by harbouring them.

Photos of encounters between prisoners of war or forced labourers and Germans during the Second World War

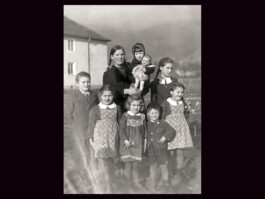

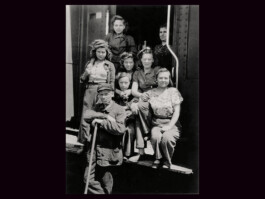

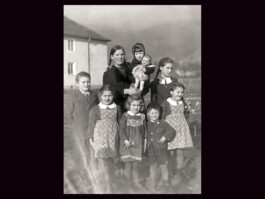

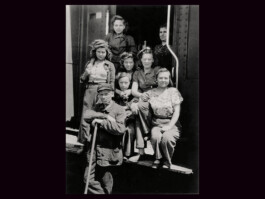

A Ukrainian forced labourer with the children of a family in Innsbruck, Austria, 5 January 1943

Elena Altayeva was 18 years old when she was deported from her home village in Ukraine to Innsbruck in 1942. As a maid for an Austrian family, she had an inside view of the family’s everyday life and private sphere. The picture shows her with seven of the family’s eight children. She sent it as a postcard to her relatives in the Ukraine. After the war, she returned to Ukraine and lived in Zhashkiv.

Photo: unknown. Memorial Research and Education Centre, Moscow

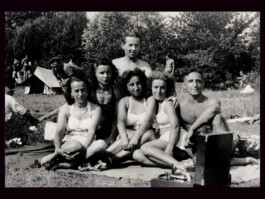

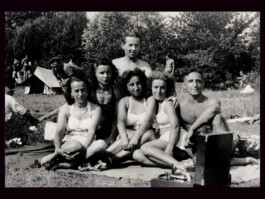

French forced labourers and German women in Leipzig, summer 1943

Forced labourer Charles Lecomte (centre back) was forced to work on a manor in Leipzig-Wahren. He was housed in Haus Auensee, a former event hall. Many photos document his leisure time in Leipzig together with other forced labourers and Germans. He supposedly had a relationship with a German woman, which resulted in a child. Despite intensive research, Charles Lecomte’s children in France were unable to locate the German woman and the child.

Photo: unknown. Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial; private property Lecomte

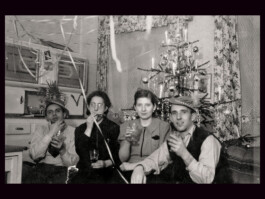

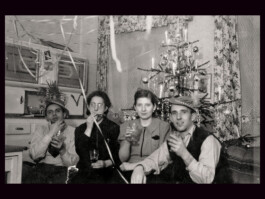

New Year’s Eve celebration of forced labourers and Germans in Merseburg, 1 January 1943

Lyubov Korchevskaya was deported from her village of Komyshuvakha in Ukraine in 1942 to Leuna in today’s Saxony-Anhalt for forced labour. She became friends with the Germans Herbert and Rosa (presumably both on the left), whom she visited in their summer house. This is where they celebrated New Year’s Eve 1942 together with other forced labourers. Lyubov Korchevskaya is not in the picture, as she probably took the photo. She returned to Ukraine after the war and lived in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

Photo: presumably Lyubov Korchevskaya . Research and Education Centre “Memorial”, Moscow

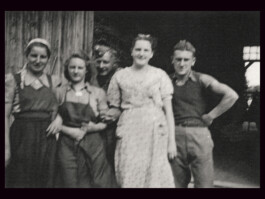

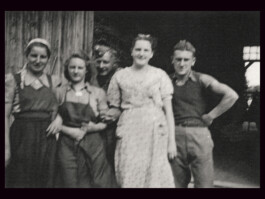

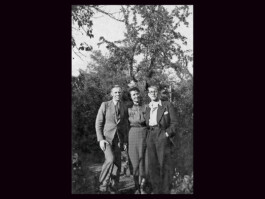

A Belgian prisoner of war with Germans on a farm in Harsefeld near Buxtehude, undated

Georges Rovillard (right) became a German prisoner of war in May 1940. He was sent to Stalag X B Sandbostel and stayed on a farm in Harsefeld near Buxtehude in the north-east of today’s Lower Saxony for almost five years. His relationship with the German family was so good that the descendants met in Harsefeld and Belgium until into the 2000s.

Photo: unknown. private property Rovillard

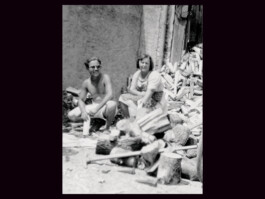

A French prisoner of war with a German farmer’s wife on her farm in Schwarzach in Baden, summer 1942

Paula P. from Schwarzach (today a district of Rheinmünster) had been widowed since 1939. In 1940, the French prisoner of war Marc G. was assigned to her farm. A year later, he was followed by the French prisoner of war Emile L. She had a relationship with both of them, for which she was convicted in October 1942. The criminal proceedings were based on photos that showed her with the men, as in this picture.

Photo: unknown. State Archives of Baden-Württemberg, Staatsarchiv Freiburg

Polish forced labourers with a German foreman in Cologne, between 1942 and 1943

The picture shows Polish forced labourers and a German foreman at a Deutsche Reichsbahn wagon at the Cologne-Deutzerfeld depot. This was presumably their place of work. The circumstances of the photograph are unknown.

Photo: unknown. NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne

French prisoners of war and German women at the Monument to the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig, 28 May 1944

The French prisoners of war Jean Gonet (second from left) and Paul Pihier (fourth from left) were forced to work for the HASAG armaments company in Leipzig. Both had their status changed to “civilian labourer”. In Leipzig, Jean Gonet acquired a camera in a trade. Among other things, he took pictures like this one of German women in front of the Monument to the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig.

Foto: Jean Gonet. Gedenkstätte für Zwangsarbeit Leipzig, Privatbesitz Gonet

Dutch forced labourers with a German woman in Leipzig, 1943

The Dutch forced labourer Henricus Corvers had to work at the post office in Leipzig. He was housed in a camp in Leipzig-Stötteritz. In the picture, he can be seen on the right with Mrs Meyer, who worked in this forced labour camp, and presumably another forced labourer. Seventy years later, his Dutch family learnt that he had had a love affair with a German woman and that they had a child together. However, the family was unable to locate the German woman and the child.

Photo: unknown. Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial, private property Corvers

French forced labourers and Germans at the works party of the Metropol cinema in the city of Brandenburg, summer 1943

The photo served as evidence in the trial against Elisabeth K., who was accused of having a love affair with Pierre H. The two can be seen next to each other in the picture (marked). During the investigation, two other men were identified as French prisoners of war in addition to Pierre H. Despite a prohibition, they had taken part in the works party.

Photo: unknown. Brandenburg Main State Archive

“A sandwich—one year in prison; a kiss – two years in prison; sexual intercourse – off with your head.”

Walter Müller, president of the Regional Court of Cologne, on what he saw as an excessively lenient judgement in the case of a German woman who had given a sandwich to a prisoner of war, between 1939 and 1945

Encounter sites

Many contacts arose at work on farms and in urban factories. They varied greatly depending on whether the person involved was a prisoner of war or civilian worker and on their nationality. Western European forced labourers, who had more freedom of movement, were able to meet Germans more easily in public —for example, outdoors in their free time. For prisoners of war and Eastern European forced labourers, meetings were more likely to occur in the countryside, as there was less surveillance. In some cases, people in the milieu deliberately looked the other way and thus allowed contacts to develop.

Spectators at a public humiliation on the market square in Ulm, 24 September 1940

Erna Ritz had a love affair with a French prisoner of war and was pregnant by him. Many onlookers turned up to watch when her head was shaved in public.

Stadtarchiv Ulm

Prosecution and penalties

In the case of illegal contact, both the Germans as well as the prisoners of war and forced labourers faced the threat of severe penalties. Different penalties applied depending on the status and nationality of the prisoners of war and forced labourers. They ranged from imprisonment or penal servitude, to internment in a concentration camp, and to the death penalty. Compared to their counterparts from Western Europe, prisoners of war and forced labourers from Poland and the Soviet Union usually faced more severe punishments, including public execution. As a deterrent, other forced labourers were often forced to watch the hangings. In some instances, on the other hand, authorities reviewed whether forced labourers were eligible for “Eindeutschung” (Germanisation)—for example, in the case of Poles with German ancestors. German men who had relationships with female forced labourers were rarely punished and usually less severely.

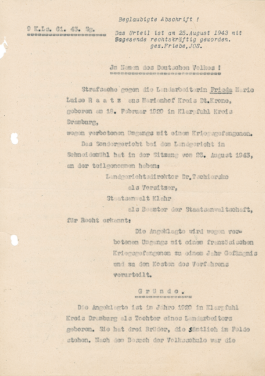

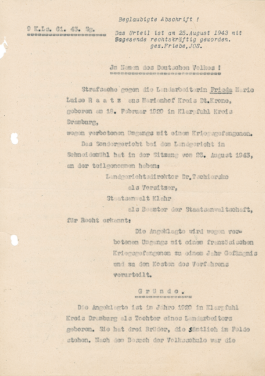

Verdict against Frieda Raatz from Marienhof in Pomerania, today's Łowicz Wałecki in Poland, 25 August 1943

Frieda Raatz was sentenced to one year in prison for her relationship with the French prisoner of war Marcel Le Néchet, which led to the birth of Gerd Raatz.

Landeshauptarchiv Schwerin

Forbidden relationships

Advisory notice signed by Yugoslav prisoners of war, 22 August 1941

The prisoners of war were cautioned in Serbian that relationships with German women or girls were punishable by ten years in prison or death.

Stadtarchiv Eutin

Close contact between Germans and prisoners of war was forbidden for reasons of military and political security. Contact with forced labourers was generally undesirable, and contact with those stigmatised as “fremdvölkisch” (ethnically foreign) was also forbidden for racist reasons.

Under an initial ordinance issued as early as November 1939, “forbidden contact with prisoners of war” beyond communications necessary for work was punishable with imprisonment or Zuchthaus (penal servitude). Further regulations followed with the “Polen-Erlasse” (Polish Decrees) of 1940 and the “Ostarbeiter-Erlasse” (Eastern Workers Decrees) of 1942. Among other things, they made relationships and love affairs with Germans a severely punishable offence. In order to prevent male Western European forced labourers from having sexual contact with Germans, the Nazi regime started setting up brothels for them in 1939.These brothels only used women

considered “ethnically foreign” to perform the sexualised forced labour.

Despite the threats of punishment, there were numerous encounters, including sexual contact and love affairs. In many cases, offenders were denounced by people from their immediate environment, for example by work colleagues. The accused were subsequently often publicly humiliated and subjected to degrading interrogations.

Ordinance Supplementing the Penal Provisions for the Protection of the Military Strength of the German People of 25 November 1939, extract

Germans were threatened with imprisonment or penal servitude for “illegal contact with prisoners of war”.

Berlin State Library

Forms of relationships

There were many different types of contact between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers. It might be an exchange of cigarettes or food or a friendly chat. This in turn could develop into a romantic relationship or sexual contact, whether in the context of a love affair or sex work. Not all sexual contact was consensual; it ranged from sexual bartering to psychological pressure in the workplace and to rape. In some cases, Germans also helped prisoners of war or forced labourers to escape by giving them civilian clothes or forged documents or by harbouring them.

Fotos von Begegnungen zwischen Kriegsgefangenen oder Zwangsarbeiter*innen und Deutschen während des Zweiten Weltkrieges

A Ukrainian forced labourer with the children of a family in Innsbruck, Austria, 5 January 1943

Elena Altayeva was 18 years old when she was deported from her home village in Ukraine to Innsbruck in 1942. As a maid for an Austrian family, she had an inside view of the family’s everyday life and private sphere. The picture shows her with seven of the family’s eight children. She sent it as a postcard to her relatives in the Ukraine. After the war, she returned to Ukraine and lived in Zhashkiv.

Photo: unknown. Memorial Research and Education Centre, Moscow

French forced labourers and German women in Leipzig, summer 1943

Forced labourer Charles Lecomte (centre back) was forced to work on a manor in Leipzig-Wahren. He was housed in Haus Auensee, a former event hall. Many photos document his leisure time in Leipzig together with other forced labourers and Germans. He supposedly had a relationship with a German woman, which resulted in a child. Despite intensive research, Charles Lecomte’s children in France were unable to locate the German woman and the child.

Photo: unknown. Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial; private property Lecomte

New Year’s Eve celebration of forced labourers and Germans in Merseburg, 1 January 1943

Lyubov Korchevskaya was deported from her village of Komyshuvakha in Ukraine in 1942 to Leuna in today’s Saxony-Anhalt for forced labour. She became friends with the Germans Herbert and Rosa (presumably both on the left), whom she visited in their summer house. This is where they celebrated New Year’s Eve 1942 together with other forced labourers. Lyubov Korchevskaya is not in the picture, as she probably took the photo. She returned to Ukraine after the war and lived in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

Photo: presumably Lyubov Korchevskaya . Research and Education Centre “Memorial”, Moscow

A Belgian prisoner of war with Germans on a farm in Harsefeld near Buxtehude, undated

Georges Rovillard (right) became a German prisoner of war in May 1940. He was sent to Stalag X B Sandbostel and stayed on a farm in Harsefeld near Buxtehude in the north-east of today’s Lower Saxony for almost five years. His relationship with the German family was so good that the descendants met in Harsefeld and Belgium until into the 2000s.

Photo: unknown. private property Rovillard

A French prisoner of war with a German farmer’s wife on her farm in Schwarzach in Baden, summer 1942

Paula P. from Schwarzach (today a district of Rheinmünster) had been widowed since 1939. In 1940, the French prisoner of war Marc G. was assigned to her farm. A year later, he was followed by the French prisoner of war Emile L. She had a relationship with both of them, for which she was convicted in October 1942. The criminal proceedings were based on photos that showed her with the men, as in this picture.

Photo: unknown. State Archives of Baden-Württemberg, Staatsarchiv Freiburg

Polish forced labourers with a German foreman in Cologne, between 1942 and 1943

The picture shows Polish forced labourers and a German foreman at a Deutsche Reichsbahn wagon at the Cologne-Deutzerfeld depot. This was presumably their place of work. The circumstances of the photograph are unknown.

Photo: unknown. NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne

French prisoners of war and German women at the Monument to the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig, 28 May 1944

The French prisoners of war Jean Gonet (second from left) and Paul Pihier (fourth from left) were forced to work for the HASAG armaments company in Leipzig. Both had their status changed to “civilian labourer”. In Leipzig, Jean Gonet acquired a camera in a trade. Among other things, he took pictures like this one of German women in front of the Monument to the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig.

Foto: Jean Gonet. Gedenkstätte für Zwangsarbeit Leipzig, Privatbesitz Gonet

Dutch forced labourers with a German woman in Leipzig, 1943

The Dutch forced labourer Henricus Corvers had to work at the post office in Leipzig. He was housed in a camp in Leipzig-Stötteritz. In the picture, he can be seen on the right with Mrs Meyer, who worked in this forced labour camp, and presumably another forced labourer. Seventy years later, his Dutch family learnt that he had had a love affair with a German woman and that they had a child together. However, the family was unable to locate the German woman and the child.

Photo: unknown. Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial, private property Corvers

French forced labourers and Germans at the works party of the Metropol cinema in the city of Brandenburg, summer 1943

The photo served as evidence in the trial against Elisabeth K., who was accused of having a love affair with Pierre H. The two can be seen next to each other in the picture (marked). During the investigation, two other men were identified as French prisoners of war in addition to Pierre H. Despite a prohibition, they had taken part in the works party.

Photo: unknown. Brandenburg Main State Archive

“A sandwich—one year in prison; a kiss – two years in prison; sexual intercourse – off with your head.”

Walter Müller, president of the Regional Court of Cologne, on what he saw as an excessively lenient judgement in the case of a German woman who had given a sandwich to a prisoner of war, between 1939 and 1945

Encounter sites

Many contacts arose at work on farms and in urban factories. They varied greatly depending on whether the person involved was a prisoner of war or civilian worker and on their nationality. Western European forced labourers, who had more freedom of movement, were able to meet Germans more easily in public —for example, outdoors in their free time. For prisoners of war and Eastern European forced labourers, meetings were more likely to occur in the countryside, as there was less surveillance. In some cases, people in the milieu deliberately looked the other way and thus allowed contacts to develop.

Spectators at a public humiliation on the market square in Ulm, 24 September 1940

Erna Ritz had a love affair with a French prisoner of war and was pregnant by him. Many onlookers turned up to watch when her head was shaved in public.

Stadtarchiv Ulm

Prosecution and penalties

In the case of illegal contact, both the Germans as well as the prisoners of war and forced labourers faced the threat of severe penalties. Different penalties applied depending on the status and nationality of the prisoners of war and forced labourers. They ranged from imprisonment or penal servitude, to internment in a concentration camp, and to the death penalty. Compared to their counterparts from Western Europe, prisoners of war and forced labourers from Poland and the Soviet Union usually faced more severe punishments, including public execution. As a deterrent, other forced labourers were often forced to watch the hangings. In some instances, on the other hand, authorities reviewed whether forced labourers were eligible for “Eindeutschung” (Germanisation)—for example, in the case of Poles with German ancestors. German men who had relationships with female forced labourers were rarely punished and usually less severely.

Verdict against Frieda Raatz from Marienhof in Pomerania, today's Łowicz Wałecki in Poland, 25 August 1943

Frieda Raatz was sentenced to one year in prison for her relationship with the French prisoner of war Marcel Le Néchet, which led to the birth of Gerd Raatz.

Landeshauptarchiv Schwerin

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.