Growing up in the post-war period

Former Polish forced labourers in a DP camp in Flossenbürg in the Upper Palatinate, 1946 or 1947

One of the largest camps for Polish displaced persons, with more than 2,000 people, was set up in the former Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in Bavaria.

Photo: unknown. Private property Danuta Grygorczyk

The German Wehrmacht’s unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945 marked the end of the Second World War in Europe. The previously forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers were no longer prosecuted. In the chaotic conditions of the early post-war period, couples found it difficult to reunite or stay together. Liberated prisoners of war returned to their home countries, while others, including many former forced labourers, were housed in camps for displaced persons (DPs) by the Allied military administration. The people in these camps were looked after by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Some of them were sent back to their home countries against their will.

It is not known how many former forced labourers and prisoners of war were able to take their children home with them. For fathers who previously had been prisoners of war or had been deported for forced labour, as well as for German fathers, the end of the war usually meant separation from their wives and children. Once released, German women who had been imprisoned for “forbidden contact” were sometimes able to return to their children if the latter had stayed with relatives. Other children, however, continued to grow up in foster or adoptive families.

American soldiers in Herten, North Rhine-Westphalia, with the daughter of a former forced labourer from the Soviet Union, 15 April 1945

It is not known whether the child was born from a forbidden relationship.

Photo: H. Budowle. The National Archives, College Park, Maryland, United States

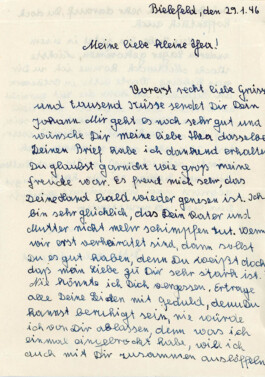

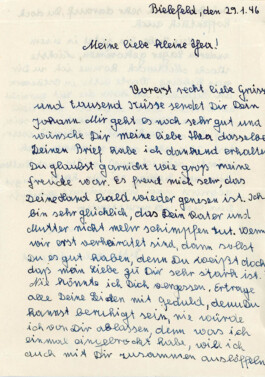

Letter from the former Polish forced labourer Johann Maciejko to Theresa (Thea) Klingenhäger, 29 January 1946

After liberation, Johann Maciejko wanted to stay in Germany with Thea Klingenhäger in order to raise their child together. However, her family opposed this. Johann Maciejko emigrated to the United States in 1947. He never saw his son Detlef again.

Private property Klingenhäger

After liberation

Even after liberation, parents of children from forbidden relationships often remained stigmatised. Reproached for having had an illegitimate child with the “enemy”, German women who returned to their hometowns from prison continued to be ostracised. Married women were also accused of adultery. Women who were merely accused of having forbidden relationships were shunned as well.

The suffering of these women remained taboo in the post-war societies of the divided Germany. Many of the women remained silent about their experiences of persecution out of shame. Former forced labourers from the Soviet Union who returned to their home countries were especially likely to be suspected of having collaborated with the Germans. They tried to keep secret their relationships with Germans and to conceal the origin of their children born from such relationships.

“In first grade, when we went home, the boys shouted ‘Polack’, ‘Polack’ at me. Then I hit them. Then it was quiet again for a while, until I maybe annoyed them again, then it was ‘Polack’ again.”

Rosa Trettin, daughter of a German woman and the Polish forced labourer Józef Trzeciak, 2015

Disputes with the authorities over children

Many children from forbidden relationships grew up in foster families after the end of the war. If mothers managed to get their children back after the liberation, they sometimes had to fight for a long time against the German authorities for custody. Others decided to place or leave their children in orphanages or foster families because of the social ostracism and lack of support.

If a couple decided to marry, the German authorities forced the women and children to take the man’s nationality. French authorities searched occupied Germany for children with a French parent in order to repatriate them to France. German mothers consequently also made false declarations so that they could keep their children.

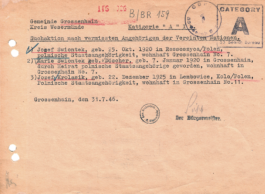

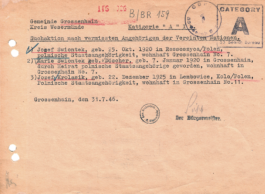

List of foreign citizens in Großenhain in the District of Wesermünde in the British occupation zone, 31 July 1946

Józef Swiontek and Marie Döscher married after the end of the war. Marie’s German citizenship was revoked when they married. In the 1950s, she and their children were able to gain citizenship in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Arolsen Archives

Eduard Spörk (back row, 4th from right) with his school class in Übersbach, Austria, 1950

At school, Eduard Spörk was insulted as a “Franzosenkind” (Frenchman’s child). When he asked his mother about the meaning of the words, she told him about his father, the former French prisoner of war Antoine Ménan.

Photo: unknown. Private property Spörk

Children’s experiences of marginalisation

Growing up without a father was not uncommon in Germany in the immediate post-war period. Many fathers had been killed in the war, found themselves as prisoners of war of the Allies, or were considered missing. However, children whose fathers were known to have been forced labourers or prisoners of war were often treated differently to most other children. For many of them, marginalisation remained part of their everyday life in their local environment even after liberation, especially at school, and sometimes even within their families. They were often stigmatised as illegitimate children and for being outside social norms. The children were repeatedly subjected to racist insults and discriminated against.

Growing up in the post-war period

Former Polish forced labourers in a DP camp in Flossenbürg in the Upper Palatinate, 1946 or 1947

One of the largest camps for Polish displaced persons, with more than 2,000 people, was set up in the former Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in Bavaria.

Photo: unknown. Private property Danuta Grygorczyk

The German Wehrmacht’s unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945 marked the end of the Second World War in Europe. The previously forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers were no longer prosecuted. In the chaotic conditions of the early post-war period, couples found it difficult to reunite or stay together. Liberated prisoners of war returned to their home countries, while others, including many former forced labourers, were housed in camps for displaced persons (DPs) by the Allied military administration. The people in these camps were looked after by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Some of them were sent back to their home countries against their will.

It is not known how many former forced labourers and prisoners of war were able to take their children home with them. For fathers who previously had been prisoners of war or had been deported for forced labour, as well as for German fathers, the end of the war usually meant separation from their wives and children. Once released, German women who had been imprisoned for “forbidden contact” were sometimes able to return to their children if the latter had stayed with relatives. Other children, however, continued to grow up in foster or adoptive families.

American soldiers in Herten, North Rhine-Westphalia, with the daughter of a former forced labourer from the Soviet Union, 15 April 1945

It is not known whether the child was born from a forbidden relationship.

Photo: H. Budowle. The National Archives, College Park, Maryland, United States

Letter from the former Polish forced labourer Johann Maciejko to Theresa (Thea) Klingenhäger, 29 January 1946

After liberation, Johann Maciejko wanted to stay in Germany with Thea Klingenhäger in order to raise their child together. However, her family opposed this. Johann Maciejko emigrated to the United States in 1947. He never saw his son Detlef again.

Private property Klingenhäger

After liberation

Even after liberation, parents of children from forbidden relationships often remained stigmatised. Reproached for having had an illegitimate child with the “enemy”, German women who returned to their hometowns from prison continued to be ostracised. Married women were also accused of adultery. Women who were merely accused of having forbidden relationships were shunned as well.

The suffering of these women remained taboo in the post-war societies of the divided Germany. Many of the women remained silent about their experiences of persecution out of shame. Former forced labourers from the Soviet Union who returned to their home countries were especially likely to be suspected of having collaborated with the Germans. They tried to keep secret their relationships with Germans and to conceal the origin of their children born from such relationships.

“In first grade, when we went home, the boys shouted ‘Polack’, ‘Polack’ at me. Then I hit them. Then it was quiet again for a while, until I maybe annoyed them again, then it was ‘Polack’ again.”

Rosa Trettin, daughter of a German woman and the Polish forced labourer Józef Trzeciak, 2015

Disputes with the authorities over children

Many children from forbidden relationships grew up in foster families after the end of the war. If mothers managed to get their children back after the liberation, they sometimes had to fight for a long time against the German authorities for custody. Others decided to place or leave their children in orphanages or foster families because of the social ostracism and lack of support.

If a couple decided to marry, the German authorities forced the women and children to take the man’s nationality. French authorities searched occupied Germany for children with a French parent in order to repatriate them to France. German mothers consequently also made false declarations so that they could keep their children.

List of foreign citizens in Großenhain in the District of Wesermünde in the British occupation zone, 31 July 1946

Józef Swiontek and Marie Döscher married after the end of the war. Marie’s German citizenship was revoked when they married. In the 1950s, she and their children were able to gain citizenship in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Arolsen Archives

Eduard Spörk (back row, 4th from right) with his school class in Übersbach, Austria, 1950

At school, Eduard Spörk was insulted as a “Franzosenkind” (Frenchman’s child). When he asked his mother about the meaning of the words, she told him about his father, the former French prisoner of war Antoine Ménan.

Photo: unknown. Private property Spörk

Children’s experiences of marginalisation

Growing up without a father was not uncommon in Germany in the immediate post-war period. Many fathers had been killed in the war, found themselves as prisoners of war of the Allies, or were considered missing. However, children whose fathers were known to have been forced labourers or prisoners of war were often treated differently to most other children. For many of them, marginalisation remained part of their everyday life in their local environment even after liberation, especially at school, and sometimes even within their families. They were often stigmatised as illegitimate children and for being outside social norms. The children were repeatedly subjected to racist insults and discriminated against.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.