Christa Steffens

born 27 February 1947

Christa Steffens grew up with several siblings with her German mother and Polish father. After the Second World War, her father stayed on the farm where he had previously worked as a forced labourer. He and the farmer’s daughter fell in love, married, and started a family. Christa Steffens’ father lived on the farm until his death.

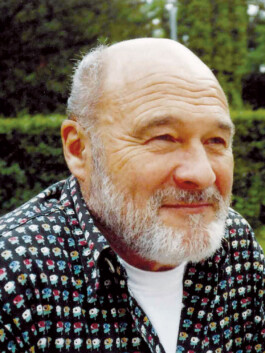

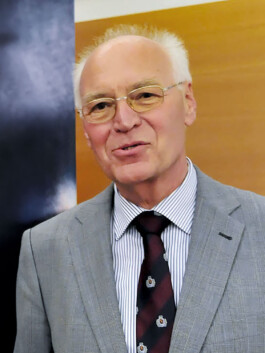

Friedrich Buhlrich

born 26 May 1946

Friedrich Buhlrich was not informed that he had been adopted until his 21st birthday. After the death of his adoptive parents, he learnt that they had had three children, all of whom had been murdered as part of the Nazi “euthanasia” programme. Friedrich’s biological parents were a German woman and a former Polish forced labourer.

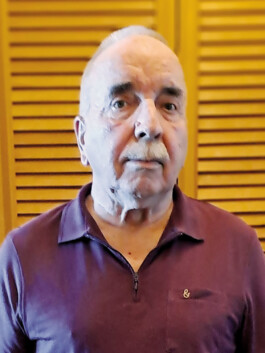

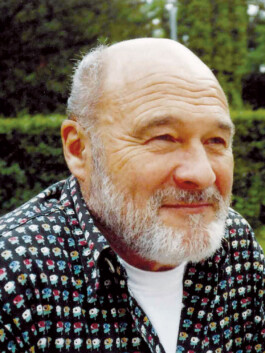

Gerd Raatz

born 20 May 1943

Until his 80th birthday, Gerd Raatz only knew the first name of his father, a French prisoner of war. With the help of the “Nevertheless here!” project team, he was able to establish contact with a half-sister in France.

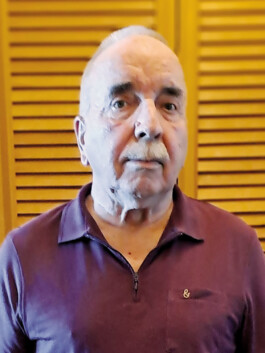

Gerd A. Meyer

born 12 November 1945

Gerd A. Meyer’s father was a Soviet prisoner of war. He died before Gerd was born. The “A”, which Gerd himself chose to include in his name, stands for Anatolyevich—son of Anatoly. In 2010, Gerd found his father’s sister and other family members in Russia and visited them there.

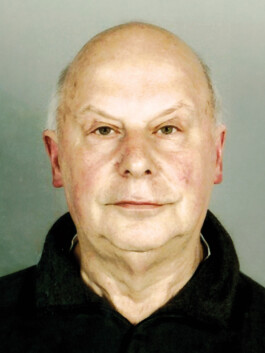

Hans Schneider

born 28 May 1943

Hans Schneider knows very little about his father, a French prisoner of war. It is said that his name was Pascal and that he looked very similar to Hans. Before the war, Hans’s father supposedly worked at the post office in Lille.

Marianne Bartl

born 19 November 1943

Marianne Bartl is the daughter of a German woman and a French prisoner of war. Her mother was sentenced to prison because of the relationship. She later had another child with another French forced labourer, Marianne’s half-sister Gabriele Lapp. Gabriele, too, is a participant in the “Nevertheless here!” project.

Peter Albert

born 3 February 1945

Peter Albert grew up believing that his stepfather was his biological father. Only on her deathbed did his mother tell him about her relationship with his father, a Polish forced labourer. She did not tell Peter his father’s name.

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit

born 18 October 1945

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit was born in a refugee camp in Salzgitter. His mother had fled there from the Sudetenland. Jack-Peter did not meet his father, a Greek forced labourer, until more than 50 years later.

Detlef Klingenhäger

born 25 June 1946

Detlef Klingenhäger’s parents met during the Second World War, when his father was deployed as a Polish forced labourer in German Reich. His father visited Detlef and his mother several times before he emigrated to the United States in 1947. After that, Detlef had no further contact with him.

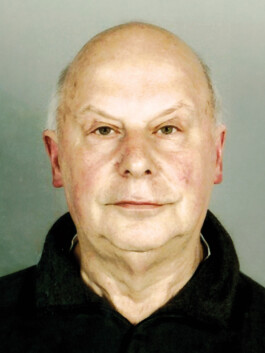

Hans Kakau

born 10 December 1942

Hans Kakau’s mother was sentenced to prison in 1943 because of her relationship with Hans’s father, a Yugoslavian prisoner of war. She never spoke to Hans about his father. After the Second World War, Hans’s aunt married a friend of his father who was likewise from Yugoslavia. The marriage did not last long and contact was broken off, so Hans never learnt his father’s name from his uncle either.

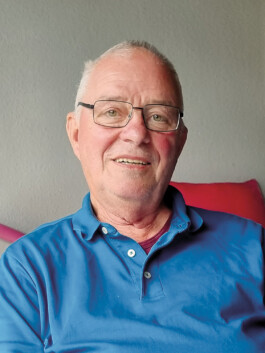

Volker Clasen

born 24 March 1943

Volker Clasen and his older sister do not know their biological father. According to insinuations made during their childhood and the results of DNA analyses, their father could have been an Italian forced labourer.

Eduard Spörk

born 23 April 1943

Eduard Spörk grew up with his Austrian mother. Only after he confronted his mother with the fact that his fellow students made fun of him as a “Frenchman’s child” did she reveal to him that his father was a French prisoner of war. After decades of searching, Eduard found his family in France. He wrote a book about his life: Franzosenkind (Frenchman’s Child).

Christa Steffens

born 27 February 1947

Christa Steffens grew up with several siblings with her German mother and Polish father. After the Second World War, her father stayed on the farm where he had previously worked as a forced labourer. He and the farmer’s daughter fell in love, married, and started a family. Christa Steffens’ father lived on the farm until his death.

Friedrich Buhlrich

born 26 May 1946

Friedrich Buhlrich was not informed that he had been adopted until his 21st birthday. After the death of his adoptive parents, he learnt that they had had three children, all of whom had been murdered as part of the Nazi “euthanasia” programme. Friedrich’s biological parents were a German woman and a former Polish forced labourer.

Gerd Raatz

born 20 May 1943

Until his 80th birthday, Gerd Raatz only knew the first name of his father, a French prisoner of war. With the help of the “Nevertheless here!” project team, he was able to establish contact with a half-sister in France.

Gerd A. Meyer

born 12 November 1945

Gerd A. Meyer’s father was a Soviet prisoner of war. He died before Gerd was born. The “A”, which Gerd himself chose to include in his name, stands for Anatolyevich—son of Anatoly. In 2010, Gerd found his father’s sister and other family members in Russia and visited them there.

Hans Schneider

born 28 May 1943

Hans Schneider knows very little about his father, a French prisoner of war. It is said that his name was Pascal and that he looked very similar to Hans. Before the war, Hans’s father supposedly worked at the post office in Lille.

Marianne Bartl

born 19 November 1943

Marianne Bartl is the daughter of a German woman and a French prisoner of war. Her mother was sentenced to prison because of the relationship. She later had another child with another French forced labourer, Marianne’s half-sister Gabriele Lapp. Gabriele, too, is a participant in the “Nevertheless here!” project.

Peter Albert

born 3 February 1945

Peter Albert grew up believing that his stepfather was his biological father. Only on her deathbed did his mother tell him about her relationship with his father, a Polish forced labourer. She did not tell Peter his father’s name.

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit

born 18 October 1945

Jack-Peter Kurbjuweit was born in a refugee camp in Salzgitter. His mother had fled there from the Sudetenland. Jack-Peter did not meet his father, a Greek forced labourer, until more than 50 years later.

Detlef Klingenhäger

born 25 June 1946

Detlef Klingenhäger’s parents met during the Second World War, when his father was deployed as a Polish forced labourer in German Reich. His father visited Detlef and his mother several times before he emigrated to the United States in 1947. After that, Detlef had no further contact with him.

Hans Kakau

born 10 December 1942

Hans Kakau’s mother was sentenced to prison in 1943 because of her relationship with Hans’s father, a Yugoslavian prisoner of war. She never spoke to Hans about his father. After the Second World War, Hans’s aunt married a friend of his father who was likewise from Yugoslavia. The marriage did not last long and contact was broken off, so Hans never learnt his father’s name from his uncle either.

Volker Clasen

born 24 March 1943

Volker Clasen and his older sister do not know their biological father. According to insinuations made during their childhood and the results of DNA analyses, their father could have been an Italian forced labourer.

Eduard Spörk

born 23 April 1943

Eduard Spörk grew up with his Austrian mother. Only after he confronted his mother with the fact that his fellow students made fun of him as a “Frenchman’s child” did she reveal to him that his father was a French prisoner of war. After decades of searching, Eduard found his family in France. He wrote a book about his life: Franzosenkind (Frenchman’s Child).

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.

nevertheless here!—Children from forbidden relationships between Germans and prisoners of war or forced labourers is a project of the Sandbostel Camp Memorial sponsored by the Foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future (EVZ Foundation) and the German Federal Ministry of Finance according to the Education Agenda NS-Injustice.

Cooperative partners are the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the project Multi-peRSPEKTif (Denkort Bunker Valentin / Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Bremen) and the Competence Center for Teacher Training Bad Bederkesa.